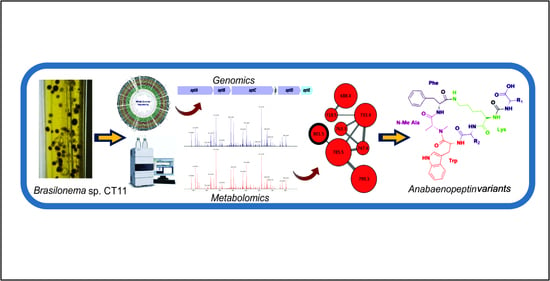

Discovery of Unusual Cyanobacterial Tryptophan-Containing Anabaenopeptins by MS/MS-Based Molecular Networking

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Cyanobacterial Strain and Culturing Conditions

3.2. Genome Sequencing, Assembling, Annotation, and Mining for Identification of Anabaenopeptin Gene Cluster

3.3. Crude Extract Preparation

3.4. HPLC-HRMS/MS Analysis

3.5. Molecular Networking

3.6. Isolation of Compound 2a and 2b from Brasilonema CT11

3.7. Antiproliferative Activity

3.8. Data Deposition

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mazard, S.; Penesyan, A.; Ostrowski, M.; Paulsen, I.T.; Egan, S. Tiny Microbes with a Big Impact: The Role of Cyanobacteria and Their Metabolites in Shaping Our Future. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schirrmeister, B.E.; Antonelli, A.; Bagheri, H.C. The origin of multicellularity in cyanobacteria. BMC Evol. Biol. 2011, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demay, J.; Bernard, C.; Reinhardt, A.; Marie, B. Natural Products from Cyanobacteria: Focus on Beneficial Activities. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dittmann, E.; Gugger, M.; Sivonen, K.; Fewer, D.P. Natural Product Biosynthetic Diversity and Comparative Genomics of the Cyanobacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saurav, K.; Macho, M.; Kust, A.; Delawska, K.; Hajek, J.; Hrouzek, P. Antimicrobial activity and bioactive profiling of heterocytous cyanobacterial strains using MS/MS-based molecular networking. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 2019, 64, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mares, J.; Hajek, J.; Urajova, P.; Kust, A.; Jokela, J.; Saurav, K.; Galica, T.; Capkova, K.; Mattila, A.; Haapaniemi, E.; et al. Alternative Biosynthetic Starter Units Enhance the Structural Diversity of Cyanobacterial Lipopeptides. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2019, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kust, A.; Mares, J.; Jokela, J.; Urajova, P.; Hajek, J.; Saurav, K.; Voracova, K.; Fewer, D.P.; Haapaniemi, E.; Permi, P.; et al. Discovery of a Pederin Family Compound in a Nonsymbiotic Bloom-Forming Cyanobacterium. Acs Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teta, R.; Romano, V.; Sala, G.D.; Picchio, S.; Sterlich, C.D.; Mangoni, A.; Tullio, G.D.; Costantino, V.; Lega, M. Cyanobacteria as indicators of water quality in Campania coasts, Italy: A monitoring strategy combining remote/proximal sensing and in situ data. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G.; Teta, R.; Marrone, R.; De Sterlich, C.; Casazza, M.; Anastasio, A.; Lega, M.; Costantino, V. A Fast Detection Strategy for Cyanobacterial blooms and associated cyanotoxins (FDSCC) reveals the occurrence of lyngbyatoxin A in campania (South Italy). Chemosphere 2019, 225, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezanka, T.; Dembitsky, V.M. Metabolites produced by cyanobacteria belonging to several species of the family Nostocaceae. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 2006, 51, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.T. Filamentous tropical marine cyanobacteria: A rich source of natural products for anticancer drug discovery. J. Appl. Phycol. 2010, 22, 659–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.C.; Monroe, E.A.; Podell, S.; Hess, W.R.; Klages, S.; Esquenazi, E.; Niessen, S.; Hoover, H.; Rothmann, M.; Lasken, R.S.; et al. Genomic insights into the physiology and ecology of the marine filamentous cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 8815–8820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nunnery, J.K.; Mevers, E.; Gerwick, W.H. Biologically active secondary metabolites from marine cyanobacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010, 21, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zanchett, G.; Oliveira-Filho, E.C. Cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins: From impacts on aquatic ecosystems and human health to anticarcinogenic effects. Toxins (Basel) 2013, 5, 1896–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caso, A.; Esposito, G.; Della Sala, G.; Pawlik, J.R.; Teta, R.; Mangoni, A.; Costantino, V. Fast Detection of Two Smenamide Family Members Using Molecular Networking. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mohimani, H.; Gurevich, A.; Mikheenko, A.; Garg, N.; Nothias, L.F.; Ninomiya, A.; Takada, K.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Pevzner, P.A. Dereplication of peptidic natural products through database search of mass spectra. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mohimani, H.; Gurevich, A.; Shlemov, A.; Mikheenko, A.; Korobeynikov, A.; Cao, L.; Shcherbin, E.; Nothias, L.F.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Pevzner, P.A. Dereplication of microbial metabolites through database search of mass spectra. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quinn, R.A.; Nothias, L.F.; Vining, O.; Meehan, M.; Esquenazi, E.; Dorrestein, P.C. Molecular Networking As a Drug Discovery, Drug Metabolism, and Precision Medicine Strategy. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2017, 38, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, K.-i.; Fujii, K.; Shimada, T.; Suzuki, M.; Sano, H.; Adachi, K.; Carmichael, W.W. Two cyclic peptides, anabaenopeptins, a third group of bioactive compounds from the cyanobacterium Anabaena flos-aquae NRC 525-17. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 1511–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welker, M.; von Dohren, H. Cyanobacterial peptides - nature’s own combinatorial biosynthesis. Fems. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 30, 530–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rounge, T.B.; Rohrlack, T.; Nederbragt, A.J.; Kristensen, T.; Jakobsen, K.S. A genome-wide analysis of nonribosomal peptide synthetase gene clusters and their peptides in a Planktothrix rubescens strain. BMC Genom. 2009, 10, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christiansen, G.; Philmus, B.; Hemscheidt, T.; Kurmayer, R. Genetic Variation of Adenylation Domains of the Anabaenopeptin Synthesis Operon and Evolution of Substrate Promiscuity. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rouhiainen, L.; Jokela, J.; Fewer, D.P.; Urmann, M.; Sivonen, K. Two alternative starter modules for the non-ribosomal biosynthesis of specific anabaenopeptin variants in Anabaena (Cyanobacteria). Chem. Biol. 2010, 17, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Koketsu, K.; Mitsuhashi, S.; Tabata, K. Identification of homophenylalanine biosynthetic genes from the cyanobacterium Nostoc punctiforme PCC73102 and application to its microbial production by Escherichia coli. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 2201–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lima, S.; Alvarenga, D.; Etchegaray, A.; Fewer, D.; Jokela, J.; Varani, A.; Sanz, M.; Dörr, F.; Pinto, E.; Sivonen, K.; et al. Genetic Organization of Anabaenopeptin and Spumigin Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in the Cyanobacterium Sphaerospermopsis torques-reginae ITEP-024. Acs Chem. Biol. 2017, 12, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, D.O.; Franco, M.W.; Sivonen, K.; Fiore, M.F.; Varani, A.M. Evaluating Eucalyptus leaf colonization by Brasilonema octagenarum (Cyanobacteria, Scytonemataceae) using in planta experiments and genomics. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, M.F.; Sant’Anna, C.L.; Azevedo, M.T.d.P.; Komárek, J.; Kaštovský, J.; Sulek, J.; Lorenzi, A.S. The cyanobacterial genus Brasilonema, gen. Nov., a molecular and phenotypic evaluation. J. Phycol. 2007, 43, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccarino, M.A.; Johansen, J.R. Brasilonema angustatum sp. Nov. (nostocales), a new filamentous cyanobacterial species from the hawaiian islands. J. Phycol. 2012, 48, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, C.D.; Hašler, P.; Dvořák, P.; Poulíčková, A.; Casamatta, D.A. Brasilonema lichenoides sp. nov. and Chroococcidiopsis lichenoides sp. nov. (Cyanobacteria): Two novel cyanobacterial constituents isolated from a tripartite lichen of headstones. J. Phycol. 2018, 54, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; Andreote, A.P.; Fiore, M.F.; Dorr, F.A.; Pinto, E. Structural Characterization of New Peptide Variants Produced by Cyanobacteria from the Brazilian Atlantic Coastal Forest Using Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 3892–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E.W.; Harper, M.K.; Faulkner, D.J. Mozamides A and B, Cyclic Peptides from a Theonellid Sponge from Mozambique. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Steinke, K.; Villebro, R.; Ziemert, N.; Lee, S.Y.; Medema, M.H.; Weber, T. antiSMASH 5.0: Updates to the secondary metabolite genome mining pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W81–W87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Luesch, H.; Hoffmann, D.; Hevel, J.M.; Becker, J.E.; Golakoti, T.; Moore, R.E. Biosynthesis of 4-methylproline in cyanobacteria: Cloning of nosE and nosF genes and biochemical characterization of the encoded dehydrogenase and reductase activities. J. Org. Chem 2003, 68, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, D.; Hevel, J.M.; Moore, R.E.; Moore, B.S. Sequence analysis and biochemical characterization of the nostopeptolide A biosynthetic gene cluster from Nostoc sp. GSV224. Gene 2003, 311, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, P.M.; Gulder, T.A.M. Direct Pathway Cloning Combined with Sequence- and Ligation-Independent Cloning for Fast Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Refactoring and Heterologous Expression. Acs Synth. Biol. 2018, 7, 1702–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.S.; Chen, W.L.; Lantvit, D.D.; Zhang, X.; Krunic, A.; Burdette, J.E.; Eustaquio, A.; Orjala, J. Merocyclophanes C and D from the Cultured Freshwater Cyanobacterium Nostoc sp. (UIC 10110). J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesner-Apter, S.; Carmeli, S. Protease inhibitors from a water bloom of the cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoof, L.; Blaszczyk, A.; Meriluoto, J.; Ceglowska, M.; Mazur-Marzec, H. Structures and Activity of New Anabaenopeptins Produced by Baltic Sea Cyanobacteria. Mar. Drugs 2015, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mares, J.; Hajek, J.; Urajova, P.; Kopecky, J.; Hrouzek, P. A hybrid non-ribosomal peptide/polyketide synthetase containing fatty-acyl ligase (FAAL) synthesizes the beta-amino fatty acid lipopeptides puwainaphycins in the Cyanobacterium Cylindrospermum alatosporum. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: Assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kessner, D.; Chambers, M.; Burke, R.; Agus, D.; Mallick, P. ProteoWizard: Open source software for rapid proteomics tools development. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 2534–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Carver, J.J.; Phelan, V.V.; Sanchez, L.M.; Garg, N.; Peng, Y.; Nguyen, D.D.; Watrous, J.; Kapono, C.A.; Luzzatto-Knaan, T.; et al. Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saurav, K.; Borbone, N.; Burgsdorf, I.; Teta, R.; Caso, A.; Bar-Shalom, R.; Esposito, G.; Britstein, M.; Steindler, L.; Costantino, V. Identification of Quorum Sensing Activators and Inhibitors in The Marine Sponge Sarcotragus spinosulus. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sample Availability: Samples of the crude extracts from Brasilonema sp. CT11 and compounds anabaenopeptin 802a and anabaenopeptin 802 b are available from the authors. |

| Product Ion Assignment | 1 (m/z) | Error, ppm | 2a/2b (m/z) | Error, ppm | 3 (m/z) | Error, ppm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lys fragment | 84.0810 | 2.6 | 84.0808 | 0.7 | 84.0808 | 0.2 |

| MeAla + CO + H+ | 114.0549 | 0.1 | 114.0551 | 1.1 | 114.0550 | 0.0 |

| Trp fragment | 130.0650 | 0.7 | 130.0653 | 1.0 | 130.0651 | 0.1 |

| Trp-MeAla + H+ | 272.196 | 0.6 | 272.1399 | 2.1 | 272.1394 | 0.6 |

| Trp-MeAla-Val + H+ | 371.2087 | 2.4 | - | - | ||

| Trp-MeAla-Ile/Leu + H+ | - | 385.2249 | 3.9 | 385.2234 | 0.0 | |

| CO-Lys-Phe-MeAla + H+ | 405.2141 | 2.1 | 405.2143 | 2.5 | 405.2138 | 1.4 |

| Val-CO-Lys-Phe-MeAla + H + | 504.2811 | 1.0 | 504.2830 | 2.7 | ||

| Ile/Leu-CO-Lys-Phe-MeAla + H + | 518.2973 | 3.0 | ||||

| Val-CO-Lys-(Val)-(Phe-MeAla) + H+ | 603.3497 | 0.6 | - | - | ||

| Val-CO-Lys-(Ile/Leu)-(Phe-MeAla) + H+ | - | 617.3677 | 4.0 | - | ||

| Ile/Leu-CO-Lys-(Ile/Leu)-(Phe-MeAla) + H+ | - | - | 631.3797 | 2.7 | ||

| Val-CO-[Lys-Val-Trp-MeAla-Phe] + H+ | 789.4304 | 1.3 | - | - | ||

| Val-CO-[Lys-Ile/Leu-Trp-MeAla-Phe] + H+ | - | 803.4469 | 2.3 | - | ||

| Ile/Leu-CO-[Lys-Ile/Leu-Trp-MeAla-Phe] + H+ | - | - | 817.4612 | 0.6 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saha, S.; Esposito, G.; Urajová, P.; Mareš, J.; Ewe, D.; Caso, A.; Macho, M.; Delawská, K.; Kust, A.; Hrouzek, P.; et al. Discovery of Unusual Cyanobacterial Tryptophan-Containing Anabaenopeptins by MS/MS-Based Molecular Networking. Molecules 2020, 25, 3786. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25173786

Saha S, Esposito G, Urajová P, Mareš J, Ewe D, Caso A, Macho M, Delawská K, Kust A, Hrouzek P, et al. Discovery of Unusual Cyanobacterial Tryptophan-Containing Anabaenopeptins by MS/MS-Based Molecular Networking. Molecules. 2020; 25(17):3786. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25173786

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaha, Subhasish, Germana Esposito, Petra Urajová, Jan Mareš, Daniela Ewe, Alessia Caso, Markéta Macho, Kateřina Delawská, Andreja Kust, Pavel Hrouzek, and et al. 2020. "Discovery of Unusual Cyanobacterial Tryptophan-Containing Anabaenopeptins by MS/MS-Based Molecular Networking" Molecules 25, no. 17: 3786. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25173786