Contents

Paul Harris Featured Articles

Accretion

Desk by Martin HorejsiJim's Fragments

by Jim Tobin Visions by John Kashuba Mitch's Universe by Mitch NodaMicro

MeteoriteWriting by Michael KellyTerms Of Use

Materials contained in and linked to from this website do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of The Meteorite Exchange, Inc., nor those of any person connected therewith. In no event shall The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. be responsible for, nor liable for, exposure to any such material in any form by any person or persons, whether written, graphic, audio or otherwise, presented on this or by any other website, web page or other cyber location linked to from this website. The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. does not endorse, edit nor hold any copyright interest in any material found on any website, web page or other cyber location linked to from this website.

The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. shall not be held liable for any misinformation by any author, dealer and or seller. In no event will The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. be liable for any damages, including any loss of profits, lost savings, or any other commercial damage, including but not limited to special, consequential, or other damages arising out of this service.

© Copyright 2002–2022 The Meteorite Exchange, Inc. All rights reserved.

No reproduction of copyrighted material is allowed by any means without prior written permission of the copyright owner.

Old Woman’s Knee, Ron N. Hartman, and NWA 400 Meteorites

Martin HorejsiAs I was doing some spring cleaning during our first Montana winter blizzard, I found a bag of meteorites labeled at Oum Rokba. Further, there was a polished complete slice with an accompanying specimen card from the Ron Hartman collection. It gave me pause since I knew Ron Hartman had passed on over a decade ago, and Oum Rokba was not a name in use much today.

Complete individuals of Oum Rokba have a unique and distinct look. They are lacking fusion crust but each has a very smooth, almost polished surface filled with macro textures. Cracks backfilled with ligher colored minerals criss-cross the landscape, and the uniform brown color varies little across specimens.

As an aficionado for those specific meteorites that land at the intersection of culture, history and space science, Oum Rokba, while a find, has created just the confusion I appreciate as a collector. The digital paper trail online for Oum Rokba is plenty deep to learn some lessons and document some takeaways.

While NWA 400, the assigned name for Oum Rokba, is a low number by today’s standards, I remember when NWA numbers were in single digits, and still shunned as a fad in meteorite naming after the “Sahara” numbers were suspect.

Oum Rokba, loosely translated as Old Woman’s Knee in Arabic is a unique weathered H5 chondrite meteorite as noted by the description in the Meteorite Bulletin: “Has a distinctive, smooth exterior devoid of fusion-crust; interior has abundant metal-grains. When purchased, was labeled as Oum Rokba. Today, it carries either of two names, but officially it is listed as NWA 400.

Born in 1935, Ron N. Hartman died on August 30, 2011 after a brief illness. While sad, the passing of Ron was after a stellar run much longer and richer than most. The outpouring of appreciation for Ron during his earthly travels are what most of us can only hope for. Doing good works that deserve recognition, and leave a healthy trail of influenced students is evidence of a life well lived. So I was pleased to see a specimen card from Ron within this bag of 20 year old meteorite specimens. And 11 years since the passing of Ron, it is clearly another example of how our individual collecting of meteorites is more a temporary curation of these 4.6 billion year old relics of our origin than a personal historic event.

Looking through the Fallen Stars list on the IMCA website, It reads to me as a history of events, and adventures in meteorite collecting. As 2022 closes the door and 2023 opens it, I am again reminded of the value of the participation from each of us as we build together this story of meteorites on Earth.

Stories like that from Ron Hartman matter, so make sure you leave some for the rest of us.

Until next time….

Fascinating CV3s

James Tobin

I love Allende meteorites. They are a famous CV3 carbonaceous and a favorite of mine. And after forty years of meteorite lapidary work I have cut many kilos of Allende making hundreds and hundreds of slices. It is chondrule packed and has chondrules of all sizes and colors. It has fantastic CAIs sometimes too. But one thing that Allende as a very fresh meteorite that fell in only 1969 does not do well is take a very high shiny polish. It is porous and soft and the carbon dust from cutting and lapping can cover the surface and obscure the beauty if not repeatedly washed and rubbed down with alcohol at the end of the work. CV3-type meteorites are to this writer very special beautiful stones that tell a story like few other meteorites. Well, I was working this month on a meteorite that I think is a close challenger to the beauty and interest level of Allende.

NAGJIR 001 CARBONACEOUS CV3

Nagjir 001 is a desert find and from the look of the outside of the pieces, it has been around on Earth for a while. It is not a fresh meteorite. Maybe that time here has made the material harder or maybe it was always less porous and less soft, than Allende. Nagjir 001 takes a beautiful sparkling high polish. It still has the dark gray matrix. The contrast is great for seeing all the chondrules that range from tiny to well over an eighth of an inch in diameter. Some of the desert carbonaceous meteorites have gotten so dark and stained that when highly polished the chondrules disappear from view. The only thing to do in those cases is leaving slices and endpieces smooth, but not polished so the chondrules will show well. With Nagjir 001 being solid and hard it has the added benefit of allowing the stone to be cut thinly. This makes for more slices and a better price for pieces with a large surface area. There is an increase in the cutting waste a bit. I think it is a far trade-off. The Nagjir stones have a few cracks which generate smaller pieces too for those who desire them. But all pieces are rich in chondrules and take that great polish. Not every piece of Nagjir 001 has giant CAIs but some slices have many CAIs visible on their faces. Most big slices will have at least one. And mixed in with the chondrules are many very small CAIs.

I have written before about having trouble making a great thin section out of Allende because it is so soft. I have the same problem with the occasional achondrite that is soft. I have two different eucrites queued up to make thin sections out of. One is very hard and needs nothing but lapping and polishing to 30 microns. The other eucrite is soft and I have already tried making thin sections of it with poor results. When I try again on the soft one I will impregnate the wafer with a hardener that will be easily absorbed into the porous eucrite matrix. This will be the first time I have tried to do this. I will write something in the future about how it works out. With soft meteorites, the thin section gets to just where it is about right then whoosh some of the last of that important 1.8 thousandths of an inch just disappears. I am left with a hole in the thin section. When I saw the Nagjir 001 and had a chance to cut and lap pieces and realized it was hard I had an instant hope that it could be used to make those great CV3 thin sections I have wanted to create for a few years.

Here are a pair of images of Nagjir 001 showing the abundance of chondrules and small CAIs.

In the following pair of images, I have focused on larger CAIs that were on the slices.

At the time of this writing, there were 594 CV3s in the Meteoritical Bulletin database. It is not an uncommon meteorite type. Some of the members of the class are historic and famous. Many are spectacular looking. Many are also expensive and hard to acquire. And if you were able as a collector to get a piece you might not want to grind it up making a thin section. Nagjir 001 however, is not historic or famous and is modestly priced, but it does have much going for it visually both in hand examination and under magnification.

I prepared three pieces of Nagjir 001 for mounting on glass slides. They needed lapping on one side to 3000 grit on a diamond disc and then polishing with 100k mesh diamond polish. This was mostly to guarantee the wafers were perfectly flat as well as to polish the side that would be glued to the glass slides. After that, I needed to do a good cleaning with alcohol and never touch the surface to be glued again with ungloved fingers. I have never written in detail about the process I use to make homemade thin sections except in one of my books on meteorite preparation. So here we go this is my homemade thin section method. After more than one hundred thin sections having been made some of the tools are showing some wear and need a refreshing you can see that in the images. But I lean on them less now and have a better feel for how to proceed without so much homespun technology.

The thin wafers are clamped to the glass slides with small spring clamps to insure a flat glue job with perfect contact free of bubbles or voids. The spring clamps also push out any extra adhesive which is mostly cleaned off the perimeter of the meteorite wafer before it has

completely cured.

The glass slides are mounted on grinding fixtures that hold the meteorite wafers level as they are ground down. Primary grinding with 360 grit removes the bulk of the material and is continued until just a bit of light can be seen through the meteorite wafer. Using thick glass discs for the fixtures serves a dual purpose. First, it makes holding the slides easy and flat as they are ground. Secondly, it makes inspection very convenient. With 600 grit the thinning continues in short intervals of grinding and inspecting. When the sliver of the meteorite is thin enough that light shows through every area well, the lapping moves to the 1500-grit disc. Work continues on the lapping machine for a short time as more light and clarity show during inspections. The slide then moves to the table where lapping is done by hand for the rest of the process. By the end, I am using my 3000 grit lap with the slide removed from the fixture and stoking the slide by hand across the disc using a few drops of water on the diamond disc. Since polishing makes a huge difference in how the slides perform I often have to polish them and then lap more with 3000 grit if it is still too thick. I may have to repeat the polishing and further lapping sequence several times. My polarized light viewer gets employed to check and recheck the thinness until the interference colors are strong and correct as close to 30 microns as I can get. I use a standard interference color chart and olivine crystals if they are there for the estimation of thinness. It is a complicated process to make thin sections by hand but doing them in batches reduces the individual time for each thin section to roughly 2 hours of work. I am sure that is more time than a commercial manufacturer takes but it is not that much time for a homebased amateur. I enjoy the process and love seeing the results when I finally get my slides to the camera to image the meteorite. If I take the time to be careful I can make nice thin sections

that are high quality, They are two sides polished, clear, and bright under the microscope or ultra-close-up camera. They have been used in classifying meteorites with success. Providing a thin section saves a couple of months of waiting for the lab to obtain one from a commercial thin section maker. It is such a pain for a lab to get them made and back that some classifiers are doing certain types of classifications without thin sections relying solely on other methods. Lunars for instance where chemistry is more important than seeing the textures are being done with microprobe and isotope analysis and less optical microscope work. I can not say my thin sections are exactly 30 microns because I have no way to measure that thin. The thickness of the glue layer is the real variable in doing a measurement. They may be a bit too thin or a bit too thick but they work and show the characteristics of the meteorite well. And my thin sections have been a joy to learn to make over the last thirty years. They were terrible at first now they are quite nice and nearly professional. I once hoped that I would not break a corner off the glass slide during my crude learning phase. Now it bothers me if I get a couple of faint scratches on the glass outside the area of the meteorite. I still have not managed to learn one thing. The type of ink to use to write in little letters the name of the meteorites remains a mystery. I am having to use tiny pieces of permanent paper labels. I have tried several India Inks and tried using my fine nib drafting pens. But it never comes out with thin sharp dense letters on the glass. I have to take the time to experiment on just that aspect of the process until I learn what the commercial makers do.

Several decades ago when I first started to make thin sections under more controlled methods I devised a few polarized light viewing tools. I made some handheld thin section holders with polarizing filters and magnifying screens that could be held up to a light and show the interference colors. I also converted some microfiche machines into thin section polarizing viewers. This is my favorite. It originally had rechargeable batteries and a charger. Those batteries gave up the ghost and crapped out long ago. I wired it up to use a big 6-volt power supply delivering several amps as the halogen projector bulb pulls a load of current. A few modifications to the microfilm carrier to accommodate crossed polarizer filters and I had this little portable viewer. It's a bit less portable now that the batteries are gone but it still takes up a lot less space on the counter than a full-size microfiche viewer. Near the end of production, I view the thin section then grind and polish and view again until I like the way the slide works. I know when I move it to the ultra close-up camera rig I will have more light, control of the filter rotation, control of the thin section rotation, and all the f/stop and shutter controls of the camera. Getting the thin section to look good in this microfiche viewer is a guarantee that I can image it well on the camera setup.

This is the nearly finished first of the three slides I had Nagjir 001 wafers for. It is nearly flat and almost thin enough in this picture. I might go back to the 3000-grit lap and take a tiny bit more off. The olivines look good though the way it is. I was surprised when I got it under the microscope to see how much of the surface was actually tiny CAIs instead of chondrules. But there were still plenty of chondrules for me to enjoy.

I have selected some images of chondrules from the thin section to finish up the article on Nagjir

001. I was not disappointed by what was in the first of the thin sections and it was the least interesting of the three wafers. I wanted to use it in case something unexpected with the material gave me problems during the making of the thin section. Then I could figure it out before making thin sections of the two much nicer pieces. I will make those soon but I have a table of other work to do that has to come first before my fun. Three bags with different lunar meteorite stones, a pair of martian meteorite stones, and a large Aba Panu wait to be cut, lapped, and polished. Also all the washings of the saw. I clean the saw after each type of Lunar or martian and collect and dry the dust keeping them all separate. That takes a lot of time. The other two slides are mounted on glass fixtures so they are ready when I have time and it will be fun to see what they have in store for me to see and enjoy.

Oriented Gao Fusion Crust

John KashubaThe Gao-Guenie fall in 1960 produced many oriented stones. I bought this small one from Marcin Cima?a and had it thin sectioned.

It has the classic shield shape from atmospheric flight.

The back has a thick vesiculated fusion crust.

The cut face is 3cm long.

Thin section in transmitted light.

There is very little fusion crust on the front surface. The back is crusted about a half millimeter thick overall.

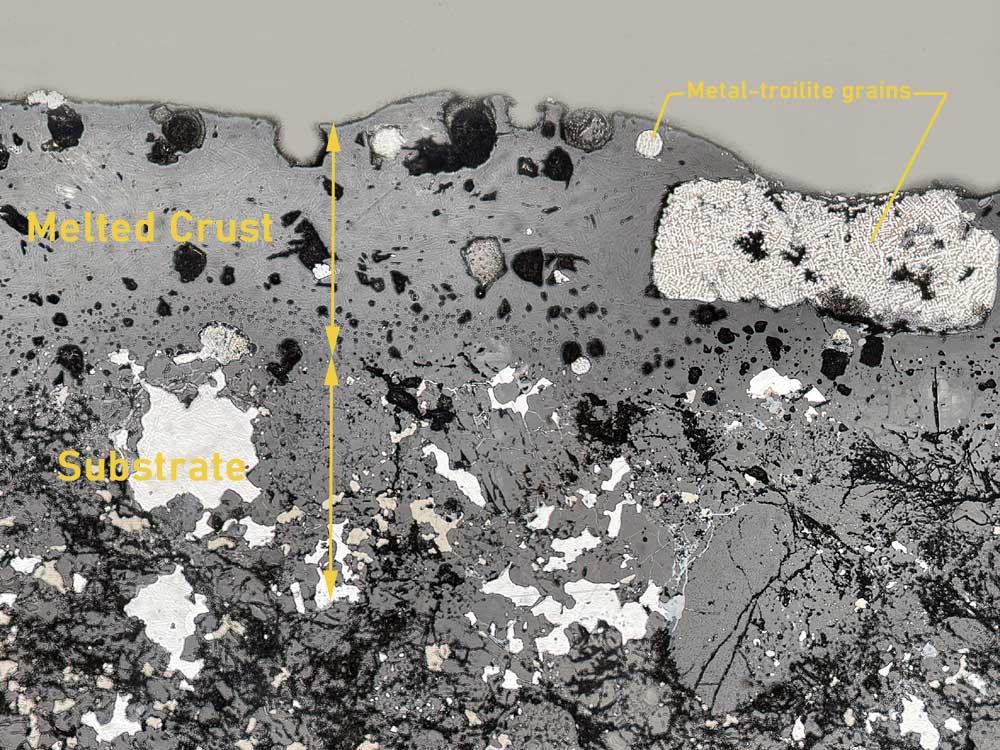

The melted crust overlies a heat affected substrate of metal veins, sulfide droplets and melted and unmelted, silicates.

The same area in cross-polarized light. Field of view is 4.3mm wide.

A different area in transmitted light. FOV=4.3mm wide.

Another 4.3mm wide area in transmitted light.

Detail of above. Reflected light.

Same area in XPL.

Another close-up in XPL.

Another close-up in XPL.

UCLA Meteorite Museum

and Alan Rubin, John Wasson and Frederick Leonard

Mitch NodaUCLA Meteorite Museum

In August 2017, I scheduled a visit to the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Meteorite Gallery (Museum) and a meeting with my friend, Dr. Alan Rubin, Curator of the UCLA Meteorite Museum. It had been decades since I stepped foot on the campus of UCLA. I remember it being a large beautiful campus when I was a freshman, but it had grown much larger. While I attended UCLA, Bruin walk was a dirt path, but now it was a nice concrete walkway. A lot had changed in over three decades. Too bad, I was not collecting meteorites back then. An interesting fact about UCLA is that according to the October 2021 U.S. News & World Report, UCLA has the highest number of people applying to the school at 108,877. As a comparison, Harvard has over 40,000 applicants, and no Ivy League school made the top ten list of applicants.

A close up of my favorite unclassified breathtaking oriented meteorite from the California meteorites display. This was a lucky find by someone in the desert not looking for meteorites, but recognizing this was an interesting rock. I believe it was used as a doorstop for a while.

The UCLA Meteorite Gallery (Museum) is located on the UCLA campus at 595 Charles E. Young Drive East in the Geology building, room 3697. It opened in January 2014. The Meteorite Gallery is open to the public and admission is free. The UCLA meteorite collection started in 1934 when William Andrews Clark donated a 357 pound (162 kg) Canyon Diablo meteorite, now known informally as the Clark iron. The collection has blossomed from the original 192 specimens that were purchased in the early 1960s from the family of Professor Frederick Leonard, who founded the UCLA Department of Astronomy. The UCLA Collection of Meteorites is the largest collection on the West Coast and contains over 3,000 specimens from 1,700 different meteorites. It is the second largest meteorite collection housed at a university in the United States, and the fifth largest collection of meteorites in the United States. The UCLA Meteorite Gallery has about 100 meteorites on display. Visitors may touch some of the big iron meteorites [Gibeon and, Camp Wood (on loan from the Utas family) as well as several large specimens of Canyon Diablo] in the Gallery, each weighing hundreds of pounds.

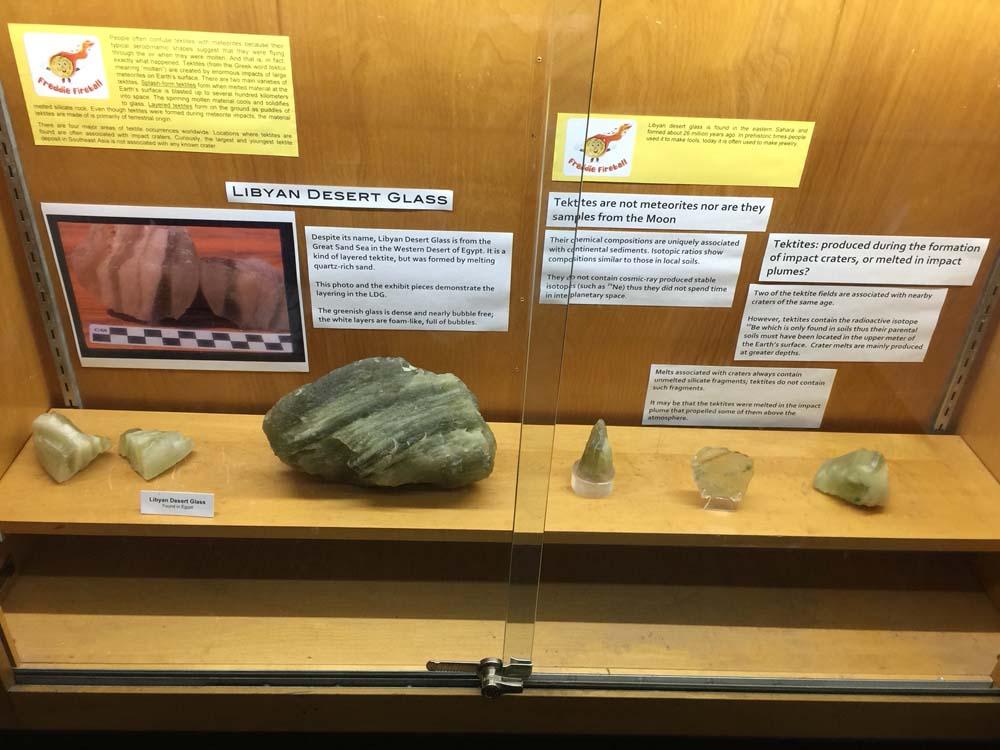

The meteorites are neatly displayed in cases. Chondrites can be found in cases 1 and 2. Some notable meteorites in these cases are La Criolla, Murchison and Allende. Case 3 houses various pallasites. Case 4 has samples of meteorites that have been partially melted or broken apart and put back together by impacts. A striking example of this is Portales Valley. Case 5 has tektites and Libyan Desert Glass. Case 6 has a selection of California meteorites. At the bottom of case 6 are “Meteorwrongs.” Case 7 has examples of melted meteorites from near surface regions. The common meteorite basalts are called eucrites. In addition, case 7 contains meteorites from the Moon and Mars.

The late John Wasson, Director of the UCLA Collection of Meteorites, explained, "The collection is important for UCLA because researchers can get samples very quickly and look at significant pieces they can hold in their hands…" It's very different than writing to a museum and asking for a small sample. With a hand specimen, you can see the shadings and textures that can tell you something about the differences in the detailed process of formation." The UCLA Collection of Meteorites provides material for research at UCLA and other universities around the world A major goal is to provide proper housing for the collection which is currently housed in ten large steel cabinets in a research lab.

Dr. Frederick Charles Leonard (1896 – 1960)

Dr. Leonard, an astrophysicist, will be forever linked with UCLA. In 1921, He earned his Ph.D. in astronomy from the University of California at Berkeley. Leonard started in the Mathematics department at UCLA. Leonard’s interest in meteorites was shared by few, if any, at UCLA at the time. He founded the Astronomy department in 1932, but was alone in studying meteoritics. He was misunderstood and unappreciated by his colleagues throughout his career. Dr. Leonard taught three rising star students – the late O. Richard Norton (Director of the Fleishman

Planetarium at University Nevada, Reno and University of Arizona, Flandrau Planetarium and Science Center, and author of the must read “Rocks from Space” – one of my all-time favorite books), the late Ronald N. Hartman (Professor of Astronomy and Director of the Planetarium at Mt. San Antonio College. He was kind and shared some of his meteorite knowledge with me.), and Ronald A. Oriti (worked for the Griffith Observatory, author of Introduction to Astronomy and wrote for Astronomy magazine). In the fall of 1937, Dr. Leonard taught a class on meteoritics, only the second time a class dedicated to meteorites was offered at any American university. We can thank him for many of the words currently in use in science today; meteoriticist and meteoritics being two of many.

After teaching at UCLA for about a dozen years, Frederick Leonard helped found The Society for Research on Meteorites the first name of The Meteoritical Society (name changed in 1946), and he became its first president in 1933. Harvey H. Nininger was the Society’s first SecretaryTreasurer. Nininger nominated Leonard to be its first president, and Leonard nominated Nininger to be its first Secretary. Leonard also nominated Dr. Oliver C. Farrington as an honorary first president. Dr. Farrington was an assistant at the Smithsonian museum and Curator at the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago; he wrote books on meteorites which Leonard used in his first class on meteorites. Later, Nininger would become president of The Society. Leonard would be the editor of the Society’s journal for the next 25 years. The Society’s Leonard medal is given to outstanding meteorite researchers. Leonard was meticulous and insisted that “Research” must be included in the title to distinguish the new Society from a hobby club. During deliberations, Leonard wanted to hold the organizational meeting at UCLA, and Nininger wanted it held in Denver. Later they received an invitation to hold the meeting at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. They decided on Chicago since it was hosting the World’s Fair at the same time.

Nininger and Leonard were friends, and Nininger visited Leonard at UCLA in August 1932. However, there was drama between Nininger, Dr. Lincoln LaPaz [in 1944, he founded the Institute of Meteoritics (IOM) at University of New Mexico] and Frederick Leonard. In 1946, Nininger and LaPaz clashed at the annual meeting of the Society for Research on Meteorites, when Nininger presented a paper discussing the scientific importance of meteorites. Nininger believed that LaPaz urged Frederick Leonard to criticize Nininger’s use of the term “meteorite,” and LaPaz went on to accuse Nininger of mounting “falsely labeled specimen[s] of worthless shale” rather than meteorites on the covers of Nininger’s “A Comet Strikes the Earth.” This led to the resignation of Nininger and his wife from The Meteoritical Society in 1949. In 1963, Nininger was persuaded to rejoin The Society.

To Leonard, his massive meteorite collection was sacred. His rigid rule of “look but don’t touch the meteorites” was enforced in his classes, and his students never touched a meteorite in class. At the time of his death, his meteorite collection was one of the largest in the world, containing samples of about one-eighth of all known meteorites. In the early 1960’s, UCLA purchased Leonard’s impressive meteorite collection from his family.

Dr. John Wasson (1934 – 2020)

Dr. John Wasson was a Professor Emeritus in the Department of Earth, Planetary and Space Sciences and Curator of the UCLA Meteorite Collection. He earned his PhD from M.I.T.,

choosing it over Harvard. Wasson joined the UCLA faculty in 1964. Wasson was the co-creator of the UCLA Meteorite Collection. Wasson was known for many things including his research involving the use of neutron activation and petrographic techniques to study chondrites and iron meteorites. He wrote two books: Meteorites: Their Record of Early Solar-System History, and Meteorites; he also published more than 300 articles on meteorites. The mineral “wassonite,” a form titanium sulfide (co-discovered by Alan Rubin) was named in his honor.

In 1966 during elections of officers of the venerable Meteoritical Society, Wasson helped lead an insurrection to remove amateur enthusiasts and replace them with professionals. He became president of the Society and was bestowed its highest honor - the Leonard Medal -- in 2002. The next year, he received the J. Lawrence Smith Medal from the U. S. National Academy of Sciences.

In later years, Wasson became interested in tektites and hunted for them in Thailand and Laos. He found they could be dispersed across a massive area and argued that it could be caused by meteoroid air-bursts, instead of the classical theory of cratering events.

In August 2017, I was fortunate to meet Wasson when I visited the UCLA Meteorite Museum. Although Wasson was in his 80’s and retired, he still biked to UCLA and worked on meteorites. I remember he and Alan Rubin were friendly and passionate about meteorites.

Tektite display.

LDG display.

Dr. Alan Rubin

Dr. Alan Rubin earned his Ph.D. in Geology from the University of New Mexico. He has been with UCLA since 1983. Rubin is a research Geochemist with the Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences. He is presently the curator of the UCLA Meteorite Collection. He is a fellow at the Meteoritical Society and winner of the Nininger Meteorite Award and seven Griffith Observer Science awards. He has conducted meteorite research on a wide variety of samples, concentrating on the nature and origin of chondrules, shock effects in chondrites and the processes that heated and altered meteorite parent bodies. Rubin has written two books on meteorites and space science including: Disturbing the Solar System (Impacts, close encounters, and coming attractions), and (with Chi Ma of Caltech) Meteorite Mineralogy. The garnet mineral – rubinite is named after him and so is the asteroid 6227 Alanrubin.

In August 2017, Alan was gracious and showed me around the UCLA Meteorite Museum. He also introduced me to John Wasson. I enjoyed spending time with both of them. They were both friendly and enthusiastic about meteorites.

Mesosiderite display.

Conclusion

If you are in the Los Angeles area, you should visit the UCLA Meteorite Museum. Dr. Rubin, Dr. Wasson, and Dr. Leonard left their indelible marks on UCLA, and the meteorite community. Acknowledgement: I would like to thank my friend, Dr. Alan Rubin, for his assistance on this article. References: Zoom call with Dr. Alan Rubin

Introduction to the Collection - The UCLA Meteorite Collection https://meteorites.ucla.edu /intro

Wikipedia: UCLA Meteorite collection

The Meteoritical Society: Personal Recollections of Frederick C. Leonard by O. Richard Norton. November 28, 2017

U.S. News & World Report: 10 Colleges That Received the Most Applications by Josh Moody. October 19, 2021.

The Meteoritical Society: “History” abstract of an article by Dr. Ursula Marvin published in 1993 in Meteoritics, volume 28, pages 261 to 314.

Wikipedia – O.C. Farrington

UCLA Newsroom: In memoriam: John Wasson, 86, cosmochemist and co-creator of the UCLA Meteorite Collection. John Harlow – September 15, 2020.

Lunar and Planetary Institute. John T. Wasson, 1934 – 2020. Text courtesy of The Meteoritical Society

https://meteorites.ucla.edu Alan Rubin – The UCLA Meteorite Collection

Daily Bruin. New mineral unearthed and named after UCLA professor by Stephen Stewart –May 3, 2011.

Junction City Georgia Fall : Technological And Social Aspects Of The Hunt

Michael KellyDear solar system, if you want to keep disrupting my writing plans ... you go right ahead! It has been quite the year so far for United States falls. I certainly am not complaining, as I love to see fresh meteorites as much as the next person.

This is the third bolide over the United States so far in 2022 that has resulted in meteorite recoveries. To put that into perspective it has been four years between this trio of falls (Cranfield, Mississippi, Great Salt Lake, Utah, and Junction City, Georgia) since the fall of Hamburg, Michigan and Glendale, Arizona in 2018. To get to a more prolific fall year you would have to go back 24 years to 1998 when four meteorites fell (Portales Valley, New Mexico, Monahans (1998), Texas, Indian Butte, Arizona, and Elbert, Colorado). So 2022 has been a boon year, and hopefully — fingers crossed with two months to go — you will hear from me in this vein of articles one more time … maybe more than that …

In that 24 years a lot has changed in the world as far as technology and its availability. These changes flow down into meteorite hunting; however, it is worth noting that a few tried and true techniques of the old hunting masters like Nininger are still highly effective. A good example is canvasing the strewn field properties with fliers to educate local land owners. This old nondigital spreading of the word increases knowledge that rocks are on the ground in the area, and coupled with a nice illustration of a fresh meteorite, helps eliminate locals gathering meteorwrongs. Contact information on a card helps get the find information over to the meteorite folks collecting data and helps to better populate strewn field maps. I have seen this work first hand, and it is still as successful today as it was back in Nininger’s day. Likewise the power of the printed and broadcast word has not fully been eliminated by the effectiveness of modern social media. A good radio interview or newspaper article on a fall shortly after its occurrence is still a valuable way to get the word out to the local community, especially where such outlets have a high viewership.

At the other end of the spectrum I could only imagine the amazement Nininger might feel chasing falls based off radar returns and doorbell camera triangulations. The digitally watched world, has come a long way towards making sure more fireballs are captured, and the amount of data per event is exponentially larger than ever before with All-Sky cameras, doorbell cameras and dash cams.

The increase in number of fireballs noticed and the better recorded details, increases the overall number of hunted bolides, and provides for a better expectation of what might have survived atmospheric entry. NASA’s interest in meteorite recovery coupled with lightning tracking satellite imagery also provides a good early indicator of an event of interest. Even software that integrates eye witness reports to triangulate a theoretical landing solution are benefits we enjoy in the U.S. that are not available for vast parts of the world.

Technology works both for and against the meteorite hunter. Sticking to the topic of cameras, a

word of caution to hunters especially in the name of keeping in the good graces of the locals on any particular hunt, and the general view of meteorite hunters in the grand scheme of things, is the woods now have “eyes.” With so many cheap available trail cameras it’s important to be cognizant of where you are and not wander onto property you don’t have permission to be on. Should you make a mistake (and it’s quite easy to do wandering through the woods with poorly marked property boundaries), being prepared and able to deescalate an inadvertent trespassing scenario is something to keep in mind.

As a meteorite hunter, once you commit to going to the strewn field, there are things out there you can do ahead of time to increase your odds of success. For instance, completing a map reconnaissance of the area to hunt has never been easier. Coming up with a hunting strategy supported by documenting your plan on a digital map by inserting pins with details allows you to save time on executing your search. Likewise, time spent at home preparing, or enroute reaching out to establish huntable areas has never been more convenient.

If the strewn field does not include much searchable public land, establishing some rapport with local landowners is the best way to gain access to huntable ground. Having the social skills to read the folks you encounter is invaluable, as not all folks will share the enthusiasm you have and be open to even having a conversation with you about anything.

For the folks willing to hear you out, or even those interested in your story, having a fresh meteorite to show, being able to effectively articulate details of the fall and why it’s important for recoveries to be made can go a long way to possibly getting you land walk access. I have found some of the most positive outreach I have done has been while on the hunt, being able to give out micros to kids and others who take interest and decide to investigate what I am up to.

If you happen to be wandering up and down roads don’t be surprised either if you catch enough local interest that law enforcement might pay you a stop even though you have done nothing wrong. Once again, having the social skills and being able to articulate what you are doing there goes a long way towards having a positive outcome.

The ease of access to sharable information has also been a major game changer towards success in hunting. With some of the greatest network coverage and prevalent use of social media and direct messaging, the fact of a huntable bolide spreads more quickly than ever before. Looking back, in 1998, 36 percent of US households had a cell phone; key in on that being households, not individuals. The spread of information on a meteorite fall back then would have been via phone, mail, and email, along with good old fashion news print and radio. Coordinates of finds would have been determined by using back azimuths to reference points on the ground and plotting the position on a paper map to get grid coordinates. GPS till the turn of the century, was really a military application, civilian GPS units cost around $3,000 and had limitations put on accuracy.

Today’s smartphones give access to GPS, allow for highly detailed and immediate photo and video documentation, and let you pin find coordinates and details in map applications. All of this information, unless you are in a very remote environment, can then be shared to targeted groups in direct messages or out to the masses on social media platforms. This allows the folks evolving strewn field maps to more quickly develop a better concept of where to continue the hunt. It also allows more data rich communication within the strewn field between individuals.

Live streaming over social media has allowed hunters to bring folks along on the hunt with them from around the world, giving virtual access to the strewn field to folks who would never be able to make it experience the hunt live and be witness to finds as they are happening. The increase in digital ability to document a find also goes a long way to having interesting provenance to go along with a piece.

Easy communication has also made coordinated logistics more common, and that improves the chances of recoveries. By eliminating unnecessary costs to individuals via shared resources, hunters can often extend the amount of time they can spend in the strewn field. I have personally diverted while on route to a location to pick up other hunters at airports, thus eliminating the need for extra rental car costs and time spent managing logistics. Likewise, by teaming up and hunting together, areas can be hunted more efficiently. Couple team hunting with “find-splitting”, sharing material found between hunters on a team, lessens the chance each individual hunter has of going home empty handed.

After walking countless miles, beating through thorn bushes, and swiping the hundredth spider web off your face, it is nice to be able to find a good meal at a place that does not have questionable reviews without having to consult the front desk staff at the local hotel. It is even better to hit that local restaurant or bar with company. Some of my most memorable moments in the strewn fields have not been finds, because let’s be honest … not all hunts turn up stones … but the camaraderie with friends old and new from other parts of the country who are sharing the experience in the field.

The Junction City Fall Details

Junction City was a meteorite finder’s type of fall. It caught interest in the hunting community by showing up on meteorite enthusiasts’ All Sky camera. That bypassed the typical two routes of catching meteorite hunters interests: The first being a posting of a fireball on social media by a non-meteorite interested person or outlet catching the eye of a meteorite enthusiast, the second being waiting for a promising log in American Fireball Network (this is event log 6491-2022 with 65 witnesses and 4 videos of the bolide by the way) to trigger some further investigation of available data.

With direct camera footage, investigation into available data such as radar returns and assessment of magnitude, speed, breakup, and the other things on videos that hunters like to contemplate when deciding if there may be rocks on the ground, happened quickly. The bolide showed up 4 minutes after midnight Eastern Standard Time on 26 September, 2022, and the first find occurred the next day, 27 September. First find photos posted to Facebook from the field is how most folks who hunted found out about the fall, with rocks already in hand. The race was then on for the second wave hunters to get to the field. As of the date of this writing (October 31st 2022) nine individual stones have been found and including all the fragments off the road smasher a total of 1.971 Kg has been recovered.

***Special thanks to Michael Doran and Ari Machiz for editorial review, and Pat Branch for a majority of the table data. Photos are credited to the submitter by initials.

Hunter: Pat Branch

How many hunts have you been on? Dozens and dozens over 15 years.

Was this your first successful hunt? No, I found some on old finds and Salt Lake was my 1st successful fresh fall. This was my most successful hunt though.

How did you find your pieces, and how did you feel when you realized you had found a meteorite? I found three stones, all visually. The first was the most amazing. I just arrived into the fall zone area and just started a drive down the road looking for the obvious stone on the road or close by the side. It was still dark as the sun had not come up yet and my headlights hit a smashed rock in the opposite lane from me. It was pretty obvious without even picking it up. The gray inside with fragments around that had black crust and I knew we had a confirmed fall. I picked up the biggest piece which was still in the dent in the road and scooped up many larger fragments that had been spread by cars. I did not do a thorough cleanup of the road at the time, figuring it would be easier later on when it was light out. I then continued to drive the roads in my fall zone.

What was one unique thing about this hunt vs the others you have been on? The most important thing was, I was the first to know that there were rocks on the ground and the first to the fall zone. By the evening of the 26th I had radar hits I was convinced were rocks in the air. I told Mike Hankey of the AMS that there was rocks on the ground in GA and I was heading there. I told fellow camera owner and Georgia resident Ed Albin where the fall zone was. I also told close by hunter Carl Dietrich.

What do you love the most about the pieces you found on this fall? I love that I found the first one and get to do the Meteorite Bulletin thing and have my name associated with the fall forever. I love that first find, which turned out to be over 670 grams total left an imprint in the road which will be a forever reminder to the locals.

Do you feel your emotional state on making a find has changed over time and if so how has it changed? I am excited every time a make a find. I have only found a handful in my lifetime, so it still excites me and amazes me that it was in space days ago.

What were a few of your most memorable non-find moments from this hunt? Getting invited to stay with the largest property owner. The Buckners were very friendly in contrast to many other locals that were very standoffish. They own much of the land under the radar hits. They are very much into history and artifacts and host a festival showcasing their many antiques every year. The patriarch, Mike cut the dent out of the road and has kept it as part of his large collection.

Any info related to the technology or social aspects of the hunt I missed you would like to highlight for the readers? One of the things I look for to see if an AMS reported event is a dropper is the seismic station data. It turned out to be a key in this fall. Often people go straight to radar and that is the easy data. But both the AMS and NASA solutions were over 20 miles from the fall zone so you might miss the radar hits. I looked at sonics and had good strong reports that put the fall zone just to the east of Junction City. So when I looked at radar I was only looking at a smaller area and was not confused with other clutter.

How many hunts have you been on? Fresh falls? Cranfield and this one. Also Bishopville and Cordova, plus quite a few fireballs where I’ve found nothing.

Was this your first successful hunt? No Cranfield was, but not anything like this one.

How did you find your pieces, and how did you feel when you realized you had found a meteorite? Pat and I had been trudging through dense forest, I had started complaining because Ed was sending us pictures of fragments found by himself and Mr. Buckner (a very kind fellow who owns a lot of the land nearby and runs the Patsiliga Museum), and I wanted to get back to collect more fragments before all the other hunters got to town.

So we started walking back to the impact pit on the road, covering opposite sides. I was a little antsy so I was moving pretty quickly, making sure to scan as best I could manage. Sitting right on the edge of the tree-line, on top of pine straw was my first individual find (the 219g). The contrast of the interior and the fresh fusion crust is unmistakable after you learn to spot it. I instantly grabbed it and started yelling to Pat and jumping up and down with my dog Piper. Knowing it was in space just 2-3 days prior and being the first person to see/hold it is absolutely incredible.

What do you love the most about the pieces you found on this fall? I love that I can see the 219g in perpetuity at the Tellus Science Museum alongside a lot of other fantastic Georgia meteorites, including the Cartersville hammer stone.

Do you feel your emotional state on making a find has changed over time and if so, how has it changed? No, I’m still just as giddy and excited every time. I usually start yelling and screaming.

What were a few of your most memorable non-find moments from this hunt? A cow road block, getting to meet Mr. Buckner, breaking down and getting my car towed, being stuck here for a week and a half, there’s definitely been a lot of them.

Any info related to the technology or social aspects of the hunt I missed you would like to highlight for the readers? My eyes were handier for hunting than any other techniques employed, rivaled by a magnet stick, but only for micros.

Hunter: Roberto Vargas

How many hunts have you been on? Junction City was my 10th, in-person, hunt.

Was this your first successful hunt? No

How did you find your pieces, and how did you feel when you realized you had found a meteorite? I had been in Junction City for about 15 minutes when I found my first stone. As I got

to the strewn field, I ran into Steve Arnold (Meteorite Men) and his friend, Lance. They were searching the far end of the strewn field and at that point no finds had been found that far southeast. I had been walking for about 10 minutes when I realized I did not have my cell phone, so I decided to turn back. As I was heading back, I spotted the stone. It was unmistakable. The fusion crust and fresh interior were in stark contrast with red dirt in the ditch that ran along the side of Matthew Rd.

What was one unique thing about this hunt vs the others you have been on? I think one of the most unique parts of this hunt was how many larger pieces were found near the road. There was a larger stone that hit the road, but then there were fragmented pieces, hundreds of feet away, in some cases. Originally, the thought was that these fragments were part of the stone that impacted the road. However, I think it is more likely that some of these larger fragments were part of a second or third stone that impacted the road and possibly trees on their way down.

What do you love the most about the pieces you found on this fall and do you feel your emotional state on making a find has changed over time? if so how has it changed?

I love my personal find the most. I kind of actually feel like this was my first find. I found pieces in Cranfield, but they were part of a stone that also hit the road, and Matt Stream actually found the first piece of that stone. This felt different because it was an individual, and not a fragment of a stone that was previously discovered by someone else. It was an awesome experience.

What were a few of your most memorable non-find moments from this hunt? I enjoyed the spirit of camaraderie among the hunters. It was also really cool getting to hang out for lunch at “Big Chick”, which happened to be the only restaurant within a 15-20 mile radius from the strewn field.

Any info related to the technology or social aspects of the hunt I missed you would like to highlight for the readers? I think a unique aspect of this hunt was how many people were willing to team up and share finds.

Hunter: Matthew StreamHow many hunts have you been on? I have been on at least 20 different meteorite hunts, most of them were cold hunts, and old falls. I’ve been on about five new fall hunts.

Was this your first successful hunt? No, I was successful in Cranfield Mississippi having found the road smasher.

How did you find your pieces, and how did you feel when you realized you had found a meteorite? The first stone I found was found using my eyes and a magnet stick together. The brush and plans made it very difficult to spot, but I saw a solid object and nice shape and I touched it with my magnet stick. The magnet stuck to it and pulled it over. My heart skipped a beat with excitement, I knew right away it was a meteorite. I immediately flipped it back to its

original position and documented its position with video, in situ photos, and GPS coordinates. I then called Mark Lyon and the rest of the team I was hunting with that day and they all came to my position and got to see where I found it and enjoy the victory!

The second stone I found with my fiancé, Luisa Contreras, and I spotted it visually laying on the grass, with shimmering blue fusion crust. We had gotten permission from Greg Rigsby to search his property and that is where we found the 231 gram stone.

The fragments I found from the road smasher were mostly found using a magnet stick, I did find a 2.5 gram and 1.3 gram fragment visually… with a total of about 15 grams found.

What was one unique thing about this hunt vs the others you have been on? The locals were very persistent about warning us about rattlesnakes and other poisonous snakes. Luisa and I got to hunt a large field on Greg Rigsby’s property with his pet donkey “DC”, he followed us around the entire field and even grabbed my backpack with his teeth and pulled me backwards for a minute.

What do you love the most about the pieces you found on this fall and do you feel your emotional state on making a find has changed over time? if so how has it changed? Both the pieces I found had a slight blue iridescence to the fusion crust, and unique beautiful shapes to them.

I love when there is a road smasher, it gives everyone a chance to find fragments, and it almost becomes the meeting point for everyone. It’s so fun to try and find broken fragments spread about the road and brush.

It’s a special feeling for me every time, it’s a euphoric feeling I can’t describe… it’s spiritual to me and it almost gets more exciting every new find!

What were a few of your most memorable non-find moments from this hunt? One of the coolest moments was watching Mr. Buckner cut the impacted road out with a saw and repave the road immediately afterwards.

The most special thing for me was finding a beautiful individual with my fiancé, it was her first time meteorite hunting and we found it our first day hunting. It’s also very special to hang with other meteorite enthusiasts, meet the locals, and enjoy the local food.

Hunter Michael Kelly:

How many hunts have you been on? This was my forth fresh fall hunt, in addition to those fresh falls I have hunted about a half dozen other old falls sites and Dense Collection Areas like western dry lake beds.

Was this your first successful hunt? This was my second successful hunt, the first one being Cranfield Mississippi earlier in the year.

How did you find your pieces and how did you feel when you realized you had found a meteorite? I found my first pieces by magnet searching around the hammer stone location. So many folks had walked around the location, that fragment had actually been compacted into the soil, by aggressively breaking up the top layer and running the magnet through it I was able to find several nicely crusted fragments. The biggest piece I found turned up while doing a visual search into the brush along the wood line on the west side of the road. I felt ecstatic when I found my piece, but since we were all grouped together when Derek found his 13 gram piece I would say my overall change in excitement was less as I was already excited and happy about that find.

What was one unique thing about this hunt vs the others you have been on? This was the first hunt where I did a fair amount of coordinating ahead of going to the field, I had originally planned to go hunt it alone. Every other hunt I have gone on, I have run into many others in the field, but for the most part, only searched with one or two other folks at a time. This time we had a group that maxed out at seven people so it was really nice to have a lot of extra socializing this go around.

What do you love the most about the pieces you found on this fall? The frothiness on the crust of this fall is amazing. I had the opportunity to make a thin section ahead of getting out and being able to hunt this fall. The chip for that thin section happened to have the tiniest bit of crust on it. Seeing how amazing the crust was in thin section made me want a nicely crusted personal find. Turns out the best piece I found happened to be from the area where the crust transitions from side smooth crust to back side frothy crust which I am very happy about.

Do you feel your emotional state on making a find has changed over time and if so how has it changed? This is only the third really cool visual find I have made. The previous meteorite, and a Bediasite find, I was so excited I impulsively grabbed the piece even though I had a well laid out plan in my mind to drop a scale cube, take pictures, etc. This time though still really excited I was glad to have my wits about me and get a few good in situ shots and enjoy the piece where it lay for a while before picking it up and giving it a good look over and weight check.

What were a few of your most memorable non-find moments from this hunt? I really enjoy talking to folks who are not into meteorites and take up an interest on an impromptu conversation. During the first few hours on site, an elderly local pulled up on the side of the road to ask us what we were doing. After giving her a brief explanation of the fact a meteorite had landed in the road and scattered fragments everywhere, she looked at me and without batting an eye said something to the effect of “bull**** I don’t believe something like that would happen here”. After a good chuckle I showed her the few fragments I had found by that point, and gave her one to remember the time a meteorite fell by her town.

Another memorable moment for me was making an unplanned donation on the second hunting day. I inadvertently donated (lost) a relatively nice micro to the strewn field that day. This is one of those scenarios where you have to get over being mad at yourself and just move on. After coming out of a particularly thorny part of the woods, a family on a utility vehicle came by and stopped to talk. They were familiar with the fall, had talked to previous hunters, and had already let other search their property. I asked them if they had done any searching and explained how fragments could be recovered with a strong magnet by the road site. When they replied they had not gotten any I went and separated out a few fragments for the kids. While fishing through my material I managed to drop the second-best crusted fragment I had found the day before.

Not a terribly huge loss, but considering we were focused that day on looking for nice individuals in the woods, I had less on hand personally at the end of the second day than the day before. A small mistake to learn from, sort and prepackage giveaways in a controlled area so you don’t have to do it in the field. The one that got away will be something I always remember.

My final memorable moment was getting to cast the impact depression left by the first find stone. Since seeing the first photo of the spot where the stone hit, I knew that the mark should be preserved as ephemera from the fall. I reached out and discussed the idea with the hunters on site, but the location is not exactly near a place that has the sort of supplies needed to get the job done right. During the 16 hour drive I stopped and gathered up all the proper materials to make a silicone impression. It felt really rewarding to make available to collectors who got hammer fragments a very detailed recreation of the impact along with being able to donate one to the Tellus Science Museum to go along with their acquisition of the 219 gram individual stone.

Ari MachizHow many hunts have you been on? One

Was this your first successful hunt? Yes

How did you find your piece(s) (visual or magnet), and how did you feel when you realized you had found a meteorite? It was kind of both visual and a magnet find. The stone was only 4.2 grams and looked very much like the other rocks on a sandy patch of ground. I was poking my magnet at each rock and one stuck.

I was so surprised, but I was really happy. There were several of us taking a break and just talking, so when I found it, all of us including me had already been standing where we were for a little while. It was nice to have everyone there. I just told everyone, "I just found one!" What do you love the most is it about the piece you found that you love the most on this fall? It was my first find, so it will always be special in that regard.

What were a few of your most memorable non-find moments from this hunt? I was really happy to meet Matthew Stream. He has been my mentor to this point, so that meant a lot to me. I also met Steve Arnold from the Meteorite Men. Because my wife found some material, Steve looked in the area and I got to hunt with him. I have to admit I got a kick out of that. Lastly, hunting with my wife was amazing. There's no way to explain how it brought out the best in her during the good and the difficult moments of the hunt. She was such a joy.

How many hunts have you been on? USA 5 recent falls Osceola second fall, Indian Butte, Cranfield, Salt Lake City and Junction City, internationally, 2 recent falls Costa Rica and Brazil. Other hunts: Holbrook, and Wilcox Playa AZ.

Was this your first successful hunt? No, Aguas Zarcas, Costa Rica massively for direct purchases over 500g and some scarce finds totaling less than 1g in micros.

How did you find your pieces, and how did you feel when you realized you had found a meteorite? For the Junction City fall we tried hunting with several new methods including a neodymium rod measuring about 1 meter in length dragged behind an electric bike around the road where the main impactor hit as well as forest hunting. We also walked private property we acquired permission to hunt in.

What was one unique thing about this hunt vs the others you have been on? One unique thing about this fall was the proximity to our home as this was the nearest to where we live (~5-hour drive) and allowed us to return frequently spending 3 to 4 days per week hunting since the fall. Despite the time and effort, we have only found one large fragment ourselves. We also teamed up with Derik Bowers for two weeks, a well-seasoned hunter, collector and dealer. I’ve learned a good deal by watching others including Derik on this hunt. One weekend we also teamed up with Carl Dietrich. Towards the end of one of the latest trips Carl’s Jeep mechanically failed and was towed and so we hunted together in our car and Carl ended up find a piece no more than 15 feet from where we parked the car locating the Easternmost individual of the fall found to date, a 6.9g individual with 70 to 80% crust exhibiting one broken side.

What do you love the most about the pieces you found on this fall? The freshness of the pieces. So far it has only rained once, to our knowledge, in Junction City and luckily the piece we collected was sitting atop some vegetation and under trees which provided good coverage.

Do you feel your emotional state on making a find has changed over time and if so, how has it changed? The biggest change is that now finds are expected rather than a surprise. I can leave the piece in place while we take in situ pictures. This hunt has been the one with the most time spent searching.

What were a few of your most memorable non-find moments from this hunt? Pulling up on a road which was miles farther than anyone had searched the strewn field Eastward and having Carl make a new individual find no more than 15 feet from the car.

Any info related to the technology or social aspects of the hunt I missed you would like to highlight for the readers? Using a combination of drone scouting, good information sharing by Pat Branch and others greatly helped the success of this hunt. Pat has been key to success we think on this hunt, identifying Doppler hits early on and sharing them in a timely fashion to the meteorite community. If Pat had not shared this information many of the pieces would likely not have been found in a timely manner before the local deer hunting season began.

Hunters Rob and Sean Keeton:

How many hunts have you been on? I have been on a fair amount of hunts but this was Sean’s first hunt.

Was this your first successful hunt? This was my second successful hunt having found two nice pieces at Cranfield. For Sean it was indeed a first success.

How did you find your pieces? I spent most of the day on the 29th of September hunting several areas in the suspected strewn field. I ended up joining Carl Dietrich and he showed me where the road impact was. I hunted there for fragments and found approximately 3.1g, which consisted of two larger pieces and small crumbs. I only had the day down there, so I had to drive home that afternoon. I gave my son Sean one of the larger fragments for his collection, gave one of the smaller pieces to a fellow in Oklahoma, and kept the rest for my collection.

What was one unique thing about this hunt vs the others you have been on? Sean kept pestering me to go hunt and I decided to take him down for a day on 3 October. This was his first real hunt in a known fresh strewn field and he was super excited. We hunted different parts of the strewn field without success, but he did find approximately 0.5g of small fragments himself at the road impact site. It was awesome to be able to make that happen for him, getting to share this with my son was certainly unique.

What do you love the most about the pieces you found on this fall? Sean is really proud of his first ever find. At one point he said, “I think I’m ready to go [home], but I can’t stop looking!” I think that means he is hooked on meteorite hunting like me. Sean has been collecting for a couple of years and loves to see his own contribution to the collection, that’s probably the best part of these pieces.

What were a few of your most memorable non-find moments from this hunt? I was pleasantly surprised with how many new faces I saw in the strewn field. I was also amazed with how the road smasher left such a distinct impression in the pavement.

Hunter Iliana:

How many hunts have you been on? This was my first.

Was this your first successful hunt? Yes

How did you find your pieces, and how did you feel when you realized you had found a meteorite? I found my pieces by magnet and I didn't know what they would look until I found one. It was the best. Adrenaline runs through your body. It brings you back to when you were a kid. It is joy and a relief. When you (Ari) paid for that teeny tiny piece, I really prayed I would find one. It is a thrill to find one. It's like we were huge adult kids. You lose your problems. Your problems are finding the meteorites, but it is a fun problem to have. It was also fun looking as a group walking together to look in a certain area.

What is it about the pieces you found that you love the most on this fall? I like the raw stone as it was cut by nature, and I love the crust. I love the little round one because it looks like a whole piece. The third one was so good because I found it at the end of the day and it was a good way to end. It was nice to find a piece that was shared with the group.

What were a few of your most memorable non-find moments from this hunt? The comradery and the excitement any time someone found something. I love when Lance found his. He told Steve Arnold to turn off the blower because he found one. It was the 120+ gram piece. That was fun.

Any info related to the technology or social aspects of the hunt I missed you would like to highlight for the readers? Nothing further.

A cast of the impact impression heading off to its new home. PC MK

Noemi Mészárosová1,2

1 Institute of Geochemistry, Mineralogy and Mineral Resources, Charles University, Albertov 6, Prague 2, CZ-12843, Czech Republic.

2 Institute of Geology of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Rozvojová 269, Prague 6 – Lysolaje, CZ-16500, Czech Republic.

As enstatite-rich meteorites, we (scientists) refer to meteorites from distinct clans, although they share some common characteristics. Enstatite-rich meteorites include enstatite chondrites (EH and EL groups), enstatite achondrites, and some anomalous ungrouped chondrites and achondrites. Enstatite-rich meteorites are relatively rare, constituting ~ 1% of all meteorite collections. Enstatite chondrites form most of these percentages, as enstatite achondrites are around six times less numerous than enstatite chondrites.

The enstatite chondrite clan belongs to the undifferentiated meteorites (chondrites). It consists of two groups EH (high iron) and EL (low iron). The dividing into these groups was first dependent on the bulk chemical composition (from these times, we have the group names); afterward, it became more dependent on mineralogy, particularly on the chemical composition of (Mg,Mn,Fe)-monosulfides, etc. Like other chondrites, the enstatite chondrites have categories referred to as the petrologic types, representing the degree of thermal metamorphosis or aqueous alteration. The number from 1 to 7 assigns the petrologic type. The most pristine (unaltered) are the chondrites of the petrologic type "3". The enstatite chondrites consist only of the petrologic types from 3 to 7 (no aqueous alteration hasn't been known for them). Some enstatite chondrites are classified as anomalous as they don't fit in any group or petrologic type. Only aubrites and ungrouped enstatite achondrites represent the clan of enstatite achondrites. One of their shared common characteristics is their mineralogy. They consist of Mg-rich pyroxene: enstatite, which has given them the name. We believe that they formed under similar highly reducing conditions. Their mineralogy reflects these conditions. Due to the reducing conditions, they consist of some rare minerals with compositions that have not been discovered on Earth yet. These minerals include sulfides of lithophile elements (on Earth) such as calcium (oldhamite: CaS), magnesium (niningerite: MgS), etc. Reducing mineralogy is also reflected in the composition of other minerals: Si-bearing kamacite (iron metal), chromium- and titaniumbearing troilite (FeS), manganese-bearing daubréelite (FeCr2S4), etc.

Enstatite chondrites and achondrites are not objects of interest only for their unique mineralogy but also for their isotopic similarities to the Earth-Moon system. The isotopic similarities (notably primitive enstatite chondrites) make them the closest potential material available to study conditions and processes in the protoplanetary disk in the region of formation of the terrestrial planets.

Due to their all similarities, widespread discussion of their common origin has been going on for many years. Although some evidence supports this claim, scientists have tended to think they

Nano-scale investigation of troilites from enstatite-rich meteorites: enigmatic witnesses of terrestrial planets formation?

did not share a common parent body in recent years. It is unclear how many parent bodies existed only for enstatite chondrites. To summarize, we do not know much about these mysterious meteorites. What were the conditions of their parent bodies' formation? How many parent bodies did they have?

Some of these questions may have answers hidden within the minerals' chemical composition and their mutual relations.

During my Ph.D. research, I have the privilege to study various meteorites from the enstatite chondrite and aubrite groups. I would like to mention some of the most interesting ones. I had an opportunity to study well-known aubrites such as Mayo Belwa, classified as impact melt breccia, or Bustee, where some scarce minerals such as osbornite (TiN) and previously mentioned oldhamite occurred for the first time. In addition, I was able to study a very famous enstatite chondrite Yamato 691 (EH3) and anomalous enstatite chondrites Yamato 86004 (EHimpact melt) or Yamato 793225 (EH6-an).

Since I focus on mineralogy, I mostly use optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), electron probe microanalysis (EPMA), and Raman micro-spectroscopy in my study, which mainly focuses on mineral troilite (FeS) and its variability in chemical composition, focusing mainly on the variation of chromium and titanium concentrations. During the extensive search for troilites and measuring their chemical composition by EPMA, I found some exciting variability in chromium concentration within the individual grains of some enstatite chondrites. Such variability could indicate the unequilibrity of these troilites in contrast to the equilibrated composition of the silicates. Similarly, in addition to the chromium concentration variation, I found the titanium concentration variation in some studied aubrites. Considering that this could lead to additional information about the formation of the parent bodies of these mysterious meteorites, I decided to look into this issue closely. Is the variability of chromium and titanium concentrations an indicator of the troilite unequilibrity, or is the cause of these phenomena hidden somewhere else? First, I decided to try more precise micro-scale observation, hoping to get some answers. Although the presence of unevenly distributed fine particles might be one of the possible answers, I was still pretty surprised when I saw the microscopic lamellas of other minerals, which were unobserved during the previous measurements, in troilite grains with a high concentration of chromium or titanium. I found less than micron-wide lamellas of mineral daubréelite as a cause of the high chromium concentration in some of the enstatite chondrites (Fig. 1) and aubrites (Fig. 2). Similarly, I found sub-micron-sized inclusions of titanium-rich sulfide heideite in the grains with high titanium concentrations in aubrites (Fig. 2). However, the elevated chromium concentration in some of the enstatite chondrites remained unexplained as I could not find any similar lamellas or inclusions. Could be the lamellas or inclusion even smaller? I needed to use an analytical technique with an even higher spatial resolution to resolve this. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) allows observation at the nano-scale. Preparation of the samples for TEM is quite complex and time-consuming as they must be electron-transparent. Because I needed to sample the selected troilite grains, I required the technique that allowed me to choose the exact location for the TEM sample preparation. Therefore I used the focused ion beam (FIB) technique. So, I prepared a set of samples consisting not solely of troilites from enstatite chondrites with unexplained high concentrations of chromium but also of troilites with the daubréelite lamellas for comparison. The observation by TEM gave some new exciting results. For example, in the cases of troilites with daubreelite lamellas observed by SEM, the daubreelite lamellas are also present at the nano-scale (Fig. 3). In contrast, otherwise, no daubréelite lamellas are found. However, the amount of data that needs to be subsequently processed is enormous. Therefore only a sample from the meteorite

Asuka 881314 has been processed. Thanks to electron diffraction patterns, I determined the mutual crystallographic orientation of troilite and daubréelite. I simulated the combined electron diffraction pattern in that mutual orientation to confirm it. This mutual orientation causes the perfect overlap of some diffraction. The exact crystal lattice parameters are required to gain such perfect overlaps. The crystal lattice parameters from electron diffraction correlate well with the simulated ones. To follow this study's outcomes, I plan to investigate this mineral assemblage of troilite-daubréelite further. To investigate their possible conditions of origin, I intend to execute experiments to synthesize troilite and daubréelite analogs and examine the extent of FeS-CrS solid solution. In conclusion, investigating minerals at their nano-scale can bring difficulties. Still, the outcomes can shed light on mineral assemblages and their texture formation. By studying such things, we can contribute to revealing the mysteries of the Universe's creation.

Acknowledgment: This research was supported by the Charles University Grant Agency project No. 1090119 and the Institutional Research Plan No. RVO 67985831 of the Institute of Geology of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague. I thank Akira Yamaguchi (NIPR) for the sample loan. Also, great gratitude goes to Petr Harcuba for the preparation of lamellas and SEM observations and to Jozef Veselý for conducting the TEM study. And last but not least, the considerable gratitude belongs to the Brian Mason Travel Award sponsored by the International Meteorite Collectors Association for the 2022 85th Annual Meeting of the Meteoritical Society held in Glasgow, UK, because thanks to this award, I was able to attend this conference in person for the first time.

Figures and their captions:

Figure 2. a) Troilite with daubéelite (dau) inclusions (indicated with arrow) in close vicinity with heideite (hei) in Yamato 793592 (aubrite) observed by SEM. b) Troilite grain with heideite (hei) inclusions (indicated with arrows) in Yamato 793592 (aubrite) observed by SEM.

NWA 11761 36.434 gram Mesosiderite

Meteorite Times Sponsors

Once a few decades ago this opening was a framed window in the wall of H. H. Nininger's Home and Museum building. From this window he must have many times pondered the mysteries of Meteor Crater seen in the distance.