Abstract

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) include social and ecological goals for humanity. Navigating towards reaching the goals requires the systematic inclusion of perspectives from a diversity of voices. Yet, the development of global sustainability pathways often lacks perspectives from the Global South. To help fill this gap, this paper introduces a participatory approach for visioning and exploring sustainable futures - the Three Horizons for the Sustainable Development Goals (3H4SDG). 3H4SDG facilitates explorations of (a) systemic pathways to reach the SDGs in an integrated way, and (b) highlights convergences and divergences between the pathways. We illustrate the application of 3H4SDG in a facilitated dialogue bringing together participants from four sub-regions of Africa: West Africa, Central Africa, East Africa, and Southern Africa. The dialogue focused on food and agricultural systems transformations. The case study results incorporate a set of convergences and divergences in relation to the future of urbanization, population growth, consumption, and the role of agriculture in the African economy. These were subsequently compared with the perspectives in global sustainability pathways, including the shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs). The study illustrates that participatory approaches that are systemic and highlight divergent perspectives represent a promising way to link local aspirations with global goals.

Export citation and abstract BibTeX RIS

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

Introduction: matching the sustainable development goals with ambitions on the ground

In 2015, the United Nations adopted the 2030 Agenda resolution with 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to shift the world onto a sustainable path. The 17 goals cover a diverse set of domains, including health, education, water, industrialization, biodiversity, and cooperation, and are set to be achieved by 2030. To successfully implement the goals, there is a need to acknowledge the diversity of contexts and perspectives in which they are to be realized. Here, participatory approaches can play a profound role.

There has been much research on the SDGs, including research that investigates interactions between goals (see, e.g., Bennich et al 2020 for a review), and research on improving national implementation of the Agenda (see reviews by Allen et al 2016, 2018, and 2021a). Recent reviews have identified research gaps that need to be filled to provide a better understanding of the Agenda and to guide its implementation. Key gaps identified include; a lack of methods that improve the understanding of interlinkages between SDGs (Allen et al 2018, 2021a), the lack of systems thinking and integrated analytical approaches and models (Allen et al 2018), a lack of systems approaches that cover the full Agenda (Bennich et al 2020), and the lack of participatory methods informed by systems thinking (Bennich et al 2020). Our research aims to fill some of these gaps by providing and showcasing a participatory approach grounded in systems thinking.

A systems approach is characterized by critically evaluating what is judged to be included and excluded in a system. An overarching systems perspective on 2030 Agenda transformations refers to seeing the Agenda as a whole and focusing on how the goals are interrelated and can be achieved together. Such a perspective is not limited to observations of facts but necessarily incorporates value evaluations about what is considered to be desirable and feasible outcomes (Collste 2021). Value evaluations are inherent in sustainability studies incorporating modeling and scenario approaches. In parallel with the implementation of the Agenda, new scenarios and models are developed, exploring pathways to sustainable futures (van Soest et al 2019, TWI2050 - The World in 2050 2018, 2019, 2020, Allen et al 2021b).

Modeling studies related to the 2030 Agenda (see, e.g., Pedercini et al 2018 and Collste et al 2017) tend to incorporate systemic understanding, typically focusing on technical aspects concerning policies that synergize for development (see, e.g., Pedercini et al 2019), and how to improve the policy strategies for reaching SDGs (see, e.g., Allen et al 2021b). However, these studies do not include more critical reflections on how divergent perspectives and worldviews affect sustainability pathways. While modeling approaches could also be used to more critically engage with divergent perspectives and explore more transformative futures, this has rarely been the case. Braunreiter et al 2021, therefore, argue for modelers to better incorporate a plurality of perspectives by engaging stakeholders. There has been a similar call to expand the scenario space by the modeling community engaged with the influential Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs), so that they better incorporate a diversity of perspectives, significantly from the Global South (see O'Neill et al 2020. Note that we are here using the terms 'Global South' and 'Global North' as defined in Mahler's 'Global South' article in Oxford Bibliographies in Literary and Critical Theory, Mahler 2017).

In a historical context, global scenarios have been only rarely explored with participation from stakeholders other than modelers. Furthermore, the involved modelers' backgrounds are often uniform, typically from universities and research institutions in the Global North. This uniformity could affect whether the models envisage futures that are grounded in perspectives originating from the Global South (Pereira et al 2018). Such limited selection of acknowledged worldviews influences both the pieces of information that are deemed relevant, but also the values that are incorporated and engrained in the scenarios and/or models. In order to counter this, and for scenarios and models to be meaningful to societies and decision-makers at different levels, sustainability-oriented scenario narratives need to reflect major tensions and debates, including both dominant and non-dominant perspectives. To facilitate this development, multiple stakeholder perspectives need to be included in the design of the scenarios (the argument behind this is further discussed and presented in Aguiar et al 2020). This is particularly relevant in the global context provided by the realization of the 2030 Agenda.

Though the 2030 Agenda embodies principles of universality, inclusion, and multi-stakeholder partnerships, it represents a top-down approach to agenda setting where goals are formulated at a high political level - to be realized across scales. The agenda has also been criticized for incorporating a uniform vision that is dominated by a narrow-minded idea of 'progress' (Victor 2019, van der Leeuw 2020), including focusing on economic growth which has been argued to contradict the achievement of other goals (Hickel 2019). This uniformity could cause a backlash in societies that are set to implement the Agenda while not fully accepting its premises (van der Leeuw 2019). To counteract such backlash, the Agenda implementation must involve sense-making processes at the national and local levels, allowing it to be translated into tangible actions specifically designed for local contexts.

It is in this context we propose a novel participatory approach that we refer to as the Three Horizons for Sustainable Development Goals, 3H4SDG. We propose this approach in order to include stakeholders rarely heard in the abovementioned contexts, to discuss pathways to the SDGs at multiple scales, with the dual goals of (a) providing input to the design of new global sustainability-oriented scenarios considering multiple perspectives across scales; (b) providing a systemic understanding of such pathways by highlighting the option space, including tensions around alternative sustainability pathways, from local to global levels. The approach builds on insights from participatory approaches, particularly the systems focus of sustainability pathways (Leach et al 2010) and the enabling features of the Three Horizons approach (Sharpe 2020). The approach, that is laid out below, is applied to the 2030 Agenda but is not limited to specific goal formulations of the Agenda as it takes an overarching systems perspective.

In this paper, we present the 3H4SDG method and lay out its steps. We also illustrate its application in a stakeholder process where the method was piloted, the African Dialogue on the World in 2050 which was held in Kigali, Rwanda, in the fall of 2018. The African dialogue focused on agriculture and food systems, a theme that spans many of the SDGs and integrates different dimensions of sustainability. The topic was identified as crucial for the region from the perspective of the funder in cooperation with local consultants, organizers, and experts. Currently, the approach is being used in many stakeholder processes since its piloting in 2018, including the applications in current case studies in Brazil, Senegal, and Spain that we briefly present in Box 2. In this paper, the approach is contextualized and discussed with a focus on the method and how it is being carried out. Subsequent studies and reports are planned to focus on different aspects of the approach and how it is being applied to new case studies.

This paper is structured as follows. We first provide a theoretical background about participatory approaches in the context of sustainability science, relating them to the 2030 Agenda. Then, we describe the participatory approach of 3H4SDG and the case study we used to pilot-test it, the African Dialogue on the World in 2050. Thereafter, we present the case study results and the participants' evaluation. Finally, we broadly discuss the approach, its applicability, and its limitations. We close the paper with our main conclusions.

Theoretical background: participation and the SDGs

Stakeholder participation has since long been emphasized in sustainability science. Participatory approaches have been incorporated in the context of adaptive management (Olsson et al 2004, Stringer et al 2006) and participatory scenario development (Oteros-Rozas et al 2015, Kok et al 2015). By involving stakeholders, a broader realm of expertise and experience is incorporated with the potential of bringing new perspectives and information. Through fair and open treatment of contested positions, the influence of knowledge on resulting actions can further be strengthened. Incorporating stakeholders thereby enables linking knowledge and action (Clark and Harley 2020). Notably, participatory approaches could support action by making participants feel empowered (Clark and Harley 2020). However, engaging with participatory approaches could also come with difficulties in traditional scientific settings. A stakeholder process could for example be difficult to meaningfully reproduce as it is dependent on various specific circumstances such as the selection of participants and the mediation style of facilitators (Folhes et al 2015). While acknowledging potential caveats and risks of participatory approaches (Sherry 1969, Leventon et al 2022), in our focus on relating SDG-related pathways to global perspectives, a core benefit of using stakeholders is to incorporate a diversity of perspectives and values in the exploration of pathways.

Participatory approaches to realize the 2030 Agenda

Incorporating stakeholder perspectives in SDG processes has been identified as a key policy challenge (see Bennich et al 2020, and Allen et al 2018, for 2030 Agenda literature reviews, see also García-Sánchez et al 2022, and Haywood et al 2019), yet currently only a few participatory approaches have been applied to 2030 Agenda studies. Examples of studies include Hutton et al (2018) who combine integrated assessment modeling in coastal Bangladesh with stakeholders to elucidate value conflicts regarding policy prioritization and trade-offs between different policies with regard to the 2030 Agenda implementation. Kanter et al (2016) provide another example of an integrated SDG study, with a focus on the Uruguayan beef sector. They use a backcasting approach that incorporates stakeholders to develop national agricultural transformation pathways. Hodes et al (2018) use participatory visual methods with HIV-positive adolescents to shed light on stakeholders' aspirations across the domains of health and social development. Glover and Hernandez (2016) take a more overarching perspective using foresight methods and imaginative storytelling involving development scholars in discussing the interactions between inequality, security, and sustainability. The approach presented by Weitz et al (2018) uses a cross-impact matrix to assess systemic and contextual interactions between SDGs and has been used in case studies in Colombia, Mongolia, and Sri Lanka (TWI2050 - The World in 2050 2020). Eichhorn et al (2021) present a multi-stakeholder approach to the 2030 Agenda implementation with a focus on integrated management and present case studies from Germany. These participatory approaches are all promising but do not explicitly incorporate global multidimensional narratives, or a diversity of worldviews, and fail to invite a wider discussion on overarching and systemic 2030 Agenda pathways.

Contesting values and narratives about transformations

Participatory pathways approaches (Leach et al 2010) are examples of structural analyses that incorporate discussions on contrasting boundaries (i.e., what to include in an analysis as 'the system'). As such, the normative nature of visions of the future is emphasized, including social justice elements. Critical questions include who participates and which contesting values and narratives are brought together (Vergragt and Quist 2011). Vergragt and Quist (2011 p. 749) challenge the futures research community by asking the rhetorical question 'Can [visioning] be left to experts, or should it be a democratic or a deliberative process involving stakeholders and citizens?'. Indeed, envisioning the future with stakeholders has the potential of lifting voices that are not heard or that are being deprived (Cvitanovic et al 2019), including voices that question the status quo. Future visioning can also play an emancipatory role for those involved, through the discovery of leverage points previously not acknowledged (Ulrich 2003, Meadows 1997). Work on adaptation pathways has also highlighted the need to recognize multitudes of actors and the need to work with a plurality of values (Fazey et al 2016).

The three horizons approach to explore possible futures

The Three Horizons is a tool to think about the future that focuses on three qualities of the future visible in the present: present dominant system features that are declining in importance, desired future features of the system, and change elements to reach a desired future. The tool has been used in participatory settings to explore possible alternative futures (Sharpe et al 2016, Colloff et al 2017, Pereira et al 2018, Sharpe 2020, Schaal et al 2023). The three horizons represent respectively (figure 1): the system to transform from (Horizon 1), the changes that are needed to break the current dominant patterns that are undesirable and to reach desirable alternative patterns (Horizon 2); and the system to transform to (Horizon 3). The Three Horizons is widely used in business management and increasingly used in research. Three Horizons brings a focus to the potential for alternative futures. It also brings an overarching frame, although it does not explicitly use systems concepts such as systems' causal structure incorporating feedback loops. In our approach, we are using elements of the Three Horizons visuals and therefore borrow its name. We propose to use the Three Horizons as a useful starting point in our pursuit of a participatory method that covers the full 2030 Agenda in a systemic way. However, as will be seen in the following section, we significantly depart from the tool by embedding it in a broader, cross-scale process focused on capturing multiple perspectives and deep-level causes of current problems. We focus on deep-level causes of problems with the understanding that to shift and transform systems, one needs to critically engage with the system structure that has brought us to where we are and develop alternatives.

Figure 1. The Three Horizons diagram shows the different horizons, steps, and post-it notes colors used during Step 1 and Step 2 of the process The Y-axis represents the level of prevalence of the features of the respective horizons (see Sharpe 2020). The X-axis represents time, in our case from the year 2020 to the year 2050. The horizons represent respectively: The system we want to transform from (Horizon 1, the red line with longer dashes), the changes that are needed to break the current dominant patterns that are undesirable and to reach desirable alternative patterns (Horizon 2, blue solid line); and the system we want to transform to (Horizon 3, green line with shorter dashes). Pink post-it notes represent society (SDGs 1–6), Yellow represents economy (SDGs 7–12), Green represents environment (SDGs 13–15), Orange represents governance (SDGs 16–17) and Blue represents changes (these are only used during Step 3). This stylized version of the diagram is intended to clarify the diagram-building process carried out with stakeholders in the participatory process. Figure 4, below, portrays a photo of the interactive version of the diagram as used in a participatory setting

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageA method to explore sustainable development pathway narratives across scales: three horizons for the SDGS (3H4SDG)

Reflecting on the context introduced above, we embarked on the following premises in designing our approach: (a) it must explicitly embrace a systems perspective of sustainability pathways; (b) it needs to facilitate the exploration of multiple and alternative pathways, including ones proposed by non-dominant voices, and narratives from different contexts and at different scales. Therefore, instead of downplaying differences in views and seeking consensus, we wanted to pinpoint divergent perspectives and bring these differences to the forefront. To fulfill (b), the participants would need to feel ownership over the process and development of pathway narratives so that the envisioned future would actually matter to them. We also wanted the process to be simple, and easily adaptable to multiple contexts and timeframes.

The approach we propose uses the Three Horizons framework to pace and facilitate conversation, enriched with cross-scale participatory scenarios methods (Zurek and Henrichs 2007, Aguiar 2015, Folhes et al 2015), pathways approaches (Leach et al 2010, Sharpe et al 2016) and creative methods, including through arts (Galafassi et al 2018). The approach discussed in this paper complements more overarching guidance on stakeholder engagement, including the United Nations training materials (see, e.g., UNESCAP 2018). The next subsections present an overview of the approach and the pilot case study.

Process outline

The process that we refer to as 'dialogue' (following Schultz et al 2016) is structured into sessions corresponding to three steps, usually adopted in backcasting exercises (backcasting is here referring to the generation of desirable futures in order to elaborate on how they can be achieved, see, e.g., Börjeson et al 2006, Quist and Vergragt 2006). Step 1 surfaces future aspirations and existing initiatives hinting at this future, Step 2 presents concerns, and Step 3 highlights necessary changes to reach the desired futures expressed in Step 1, or address present concerns identified in Step 2. Figure 2 illustrates the full process. Starting from the desired future enables participants to imagine a future without the confines of current constraints. This further avoids anchoring the discussions in today's concerns and norms and supports the exploration of what may be currently non-dominating visions, which dominant narratives would otherwise overshadow. For each step, a bigger group of participants is to be divided into smaller groups. In order for the groups to be manageable and for each participant to be able to fruitfully contribute to the dialogue, we propose around six to eight people in each group, plus two facilitators. A variety of perspectives may be represented in each group, allowing for diverse views and narratives through which to discuss the 2030 Agenda. Alternatively, one may want to separate participants from similar backgrounds in order to, at a later stage, be able to highlight differences and similarities between groups. To better reach the stated aims of the process, we suggest pre-allocating people into groups so that each group incorporates the sought diversity of perspectives.

Figure 2. The complete process to uncover multiple pathways using the 3H4SDG.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageIn each group, participants have a large Three Horizons diagram in front of them: on a table or on the ground (figure 1). The diagram is used as a visual device to facilitate conversation between the participants and to capture their ideas. The participants gradually populate the diagram with their contributions, in the form of colored post-it notes. Each step has a guiding question that can be adapted to different contexts (see the example from our pilot case study below). During the entire process, divergent perspectives are noted down by the facilitator on a board, thereafter discussed in a plenary session, and can later be analyzed by the researchers.

To ensure that a multitude of dimensions of sustainability is covered when discussing future aspirations and present concerns (steps 1 and 2), colored post-it notes can be used representing the various dimensions, e.g., society, economy, environment, and governance (this is also corresponding to the 2030 Agenda characterization by the UN Secretary-General: People, Prosperity, Planet, Peace, and Partnership, figure 1). After populating the diagram with post-it notes in Step 2, the dimensions are discussed integratively. The facilitator asks the stakeholders to analyze the deep causes underlying the present concerns: the core obstacles that are standing in the way to reach sustainability. The activities include clustering the post-its, creating a list of deep causes, including, if possible, sketching influence diagrams with the participants (influence diagrams are often referred to as causal loop diagrams, CLDs). Using influence diagrams promotes the systemic understanding of the root causes, and later in Step 3 helps identify leverage points for change.

The facilitators' roles in the process are (a) to support all participants to contribute equally, avoiding dominance of more outspoken or powerful participants; (b) to ensure that a broad range of sustainability dimensions are covered in steps 1 and 2; and (c) when disagreements among participants emerge, to note the divergences and move the process forward (avoiding long discussions about individual topics but still acknowledging the issues). The facilitators should listen, take notes and organize the discussion, but avoid interfering with their own views as this may bias the discussions.

After steps 1 and 2, exchanges between groups and a presentation of existing global perspectives on sustainability, e.g., those that are dominant in existing global scenarios, follow (figure 2). This exchange between participants can take place through a World Cafe session, in which group participants rotate between the groups allowing the sharing of results and taking note of contrasting perspectives. The exchange exposes participants to issues they may not have considered. The Global Perspectives session exposes participants to assumptions underpinning recent global scenario studies, for example, the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways, SSPs that are informing the IPCC (O'Neill et al 2017), and their implications for the context under discussion. This step is carried out through a presentation prepared by the facilitators. This session takes place after Step 2 in order to avoid constraining the thinking of participants as they brainstorm their preferred futures. Multiple perspectives may also emerge by contrasting global perspectives of the SSPs with the results of the discussions for different regions or groups of actors.

In Step 3 which is introduced after the global perspectives deliberation, each group discusses the possible actions necessary to overcome the current obstacles and reach the SDGs in an integrated manner, using single-colour post-its to indicate the potential integrative nature of actions. Participants are here asked to think about short-term and long-term actions to break the present concerns, and about deep causes and the actors behind the proposed actions. Finally, as in the other steps, the facilitators ask the participants to summarize the pathways.

As in the process described by Folhes et al (2015), at the end of each step, participants are asked to use a creative method to summarize the discussion (see figure 3). The facilitators then leave the room, and participants write a story, a letter, create hashtags, imagined newspaper headlines, draw, create a theater play, a video - or use whatever available media they prefer. The goal is to support that the participants unleash their imagination and take ownership of the process, by including their emotions in the visioning process. Imagination in participatory approaches contributes to inspiring and empowering the participants (Pereira et al 2018, 2021).

Figure 3. Illustrations of the outcomes from the 3H4SDG process. There are three outcomes per step.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe outcomes of each step are threefold: (i) the diagram with post-its across all three horizons; (ii) the list of divergences marking potentially separate pathways; (iii) the creative synthesis product (see figure 3). As described above, in the case of Step 2 of highlighting concerns, participants may create a list of root causes or create influence diagrams. In the final plenary, group results are presented, and convergences and divergences within and across the groups and in relation to the global perspectives are discussed. After the plenary, a facilitated evaluation session provides participants with time to reflect upon the dialogue process and gives organizers feedback to improve it.

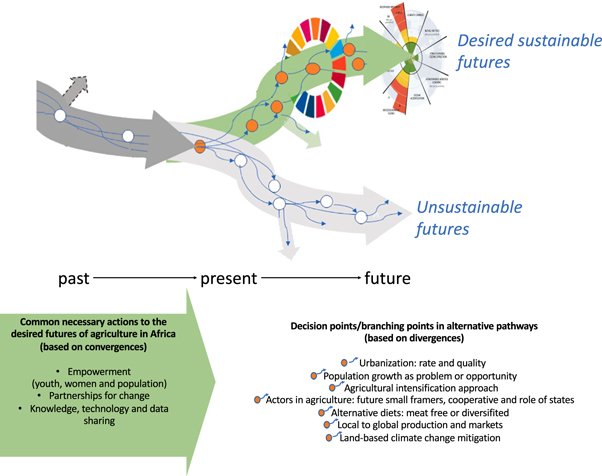

After the dialogue, the researchers transcribe and organize the outcomes, and analyze what we refer to as the convergences and divergences among the pathways. Convergences are common elements among different pathways. The convergence analysis can provide information on common premises and actions that are perceived to be commonly agreed upon parts of all pathways to sustainability. The divergence analysis aims at shedding light on multiple alternatives of sustainability pathways. Divergences may entail branching points of different future pathways as seen differently by participants (see figure 6 below). An example of branching points may concern a future society where a large part of the population lives in rural areas, and others in a more urban future, or a future in which community relations stay important, with extensive local trade transactions, versus a future in which an extensive part of products are exported and imported.

Dialogue results and analysis are structured in a report that is shared with participants in a draft form inviting them to review it before it is distributed to the wider society. In the next section, we briefly present how the approach was applied in an illustrative case study.

An illustrative case study: the African Dialogue on the World in 2050

We piloted the approach during the African Dialogue on the World in 2050, held in Kigali, Rwanda, in October 2018, over two days. Situating the dialogue in Central Africa with a pan-African focus and participants from across the continent was considered appropriate given our aim to include perspectives from the Global South. However, other localities in the Global South, including countries in Latin America, Asia, and Oceania, would also have been suitable. Placing the dialogue in this particular country was also grounded in practical reasons including already having established a node of contact through the organization SwedBio at Stockholm Resilience Centre. The dialogue focused on the safe and just operating space for humanity ('safe' and 'just' space refers to staying within the planetary boundaries and ensuring human needs, see, e.g., Häyhä et al 2016) with the overarching question: How can transforming the food and agriculture systems in Sub-Saharan African contribute to attaining the SDGs within planetary boundaries?.

The event was organized with financial support from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida, through SwedBio at Stockholm Resilience Centre. The dialogue had 40 participants (31 stakeholders and 9 facilitators) from 11 different countries, including representatives of national governments, UN organizations, civil society and local communities, academia, and research. The stakeholders were selected based on their expertise and experience (relevant to African agri-food systems and agro-biodiversity); and for having an understanding of related policy processes (e.g., social and economic development strategies, spatial planning, research-development-innovation, conservation and resource management).

The dialogue took place over a span of two days in Kigali, Rwanda, with the first two steps of the process and the World Cafe taking place on the first day, the presentation of global perspectives, the third step, the synthesis, and the evaluation, taking place the second day.

The participants were divided into four regionally focused sub-groups, based on the Sub-Saharan African regionalization of the African Union, including (i) West and Central Africa (combining the two African Union zones), (ii) East Africa, (iii) Southern Africa, and (iv) Sub-Saharan Africa to represent issues beyond sub-regions. The goal of this division was to increase the inter-group diversity of perspectives and thereby potentially enrich the cross-scale comparison (global, Africa-wide, and regional). Note that the intent here was to showcase, and shed light on, differences in perspectives. If the process is to be reiterated or followed-up one may want to, in the next step, distill similarities across groups to build commonly agreed upon scenarios that could be useful for researchers and policymakers across the board. The division of participants among the groups considered various aspects such as the location of the participant, professional background, and the practical requirement of having manageable groups (in line with the selection process of Pereira et al 2018). Diversity within groups was sought, so as to include a variety of competencies, values, and narratives within the separated regions. Each group incorporated around six stakeholders and two facilitators. Facilitators were trained to guide the process and not to contribute with expertise to the themes being discussed.

Considering the overarching theme for the Dialogue, the specific guiding questions for Step 1 were: 'What are our visions for the future of agriculture and food systems in the group region?' and 'What do you see of the desired future already existing in the present (initiatives, project, proposals etc)? The step 2 guiding question was: 'What concerns do we have about the present agriculture and food system in your group region?'. The step 3 guiding questions were: 'How do we change the present system to transform to the desired futures?' and 'Which measures and actions are required (considering the root causes)?'

The presentations of global perspectives about pathways to reach multiple goals were based on IIASA's The World in 2050 report (TWI2050 2018). These global perspectives were further deliberated, and compared to the outcome of the African Dialogue in Aguiar et al (2020). At the end of the Dialogue, an evaluation form was provided for all the participants (see Supplementary data for the form and anonymized stakeholder replies) and after the Dialogue, results were shared and compiled in a report (see Aguiar et al 2019). Next, some dialogue results are presented with emphases on convergences and divergences.

Figure 4. An illustrative photo from the African Dialogue on The World in 2050. The Three Horizons diagram on the floor is in the middle of the group discussion, with post-it notes as illustrated in figure 1.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageCase study results

Outcomes from the parallel groups

The 3H4SDG process resulted in future visions, lists of current challenges and their root causes, and lists of the changes needed to attain a sustainable future, as discussed in each group (see Appendix A in Supplementary data). The results also included a complete analysis of the divergences and convergences across the groups and in relation to the Global Perspectives (see Appendix B in Supplementary data).

Table 1. A summary of the four pathways explored during the African Dialogue on The World In 2050.

| Pathway name and unique features | Future aspirations | Present concerns & seeds of the positive future | Change actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ubuntu (West and Central Africa): Fully organic and cooperatives dominating. | Agriculture and food systems dominated by farmers' associations and cooperatives. Future characterized by diversity, inclusiveness, and agroecology. | Environmental degradation, the low interest in agriculture among youth, growing inequalities and the collapse of social values in communities. Seeds of a positive future lie in organic farming systems. | Building dynamic movements through empowered farmers' organizations and cooperatives and intensify farmers' relations and interaction for better communal agriculture. Leaving fossil resources in the ground. |

| Peaceful and Prosperous East Africa: Divergence between whether small-scale agriculture or large-scale commercial farming is dominating. | Food security assured through either small-scale agriculture or large-scale commercial farming- divergences in groups. Science collaborating with the local community to solve community problems is important. | East African countries suffer from food insecurity because production is low as a consequence of low technology adoption and inadequate investments and research. | Investments in agriculture and education enable a prosperous future. Farmers' financial resources are secured and mobilized. |

| Urugendo (Southern Africa): Focus on peace as a precondition. | Agriculture provides livelihoods, drives the economy and is run by young people. Agriculture is private-led and peace is emphasized as a precondition for a prosperous future. Farmers organized in cooperatives, no hunger. | Lack of investments in agriculture, many governance problems within cooperatives and governments are constraining a positive development. | Both cooperatives and private businesses are participating and the government provides preconditions through enabling credit and enabling legal frameworks. |

| Rainbow (Sub-Saharan Africa) : Strong focus on the role of the governments in providing institutional frameworks and regional partnerships. | An aware and educated society empowers its citizens and promotes home-grown and local knowledge. States are capable, with strong institutions that can deliver and are accountable to their citizens. Citizens are actively participating in society and collaboration platforms are provided. | Low human capital as a consequence of poor educational quality and brain drain causes high population growth. Climate change and environmental degradation threaten production and well-being. | Building infrastructure, implementing education programs, and promoting local solutions stimulate the necessary innovation. Agro-forestry is promoted and upscaling programs emphasized. Cultural and behavioral changes powered by synergies, cooperation and coordination, and increased access to finance and insurance. |

To illustrate the process outcomes, below we provide a brief introduction to the resulting visions, summarized in table 1. The West and Central Africa group named their pathway the Ubuntu pathway after popular doctrine for the quality of human interdependence and connectivity. The Ubuntu pathway describes a future of African agriculture and food systems dominated by farmers' associations and cooperatives. In this pathway, participants presented that Africa embraces its diversity, and the right to land is inclusive. Agroecology takes the lead and the farming systems are fully organic.

In the pathway developed by the group focusing on Eastern Africa, named the Peaceful and Prosperous East Africa Pathway, food security is assured through either small-scale agriculture or large-scale commercial farming, as this is one of the divergences that emerged from the process. Investments in agriculture and education enable a prosperous future. Agriculture is private-sector led and gender-balanced. Farmers are secured financial resources.

The Southern Africa group named their pathway after the Swahili and Kinyarwanda word for pathway or direction: the Urugendo pathway. In the Urugendo pathway, agriculture provides livelihoods and drives the economy. Agriculture is private-led and peace is emphasized as a precondition for a prosperous future. Both cooperatives and private businesses are participating and the government provides preconditions by enabling credit and enabling legal frameworks.

The final group had an overarching focus on Sub-Saharan Africa and named their pathway the Rainbow Pathway. In the Rainbow Pathway, an aware and educated society empowers its citizens and promotes home-grown and local knowledge. Nations are capable, with strong institutions that can deliver and be accountable to their citizens. Citizens are actively participating in society and collaboration platforms are provided. The Sub-Saharan Africa group, when compared to the sub-regional groups, emphasized more aspects related to regional cooperation, including data generation/sharing and the importance of alliances for change (across Africa and with the other continents). In the following section, we explore the convergences and divergences which emerged from the exercise. Table 2 illustrates the outcome of the creative part from one of the pathways, the Uruguendo pathway, as an illustrative example.

Table 2. Examples of creative synthesis products for different steps

| Step 1 - Future aspirations Urugendo (Southern Africa) | Step 2 - Present concerns Urugendo (Southern Africa) | Step 3 - How to get there Urugendo(Southern Africa) |

|---|---|---|

| Dear friend, | Let's check our 2018 library Newspaper Headlines: | Dear friend, |

| What a wonderful Sunday morning. Young people here are cultivating large areas of land that were once barren but have now been restored because of reforestation, water towers and through improved irrigation systems. | 1. Dairy farmers register losses due to power outage | I have received your reply to my letter asking me how we achieved our visions. Farmers, through our cooperative societies, worked closely with the government to put in place an enabling environment through the legal and policy framework that streamlined our governance systems for accountability and transparency. Through development of cooperative society's policy and enactment of cooperative Act, both productivity and aggregation of our produce increased. This translated into structured marketing and hence increased incomes for us farmers. Cooperatives empowered farmers who subsequently engaged the government to create an agriculture credit guarantee scheme in addition to creating an insurance scheme for our farmers. .... |

| 2. Farmers' cooperatives close down their businesses due to heavy taxes | ||

| 3. Disagreement in the cabinet causes farmers to lose billions of money | ||

| Currently, the farmers are organized into cooperatives and have invested and own agro-based businesses and are major exporters of agro-processed products (e.g., beer, fruit juices, etc). The youth are outstanding in agriculture and doing what they love.... | 4. Thousands of hectares of food crops destroyed by floods | |

| 5. Farmers complain of lack of appropriate techniques in dairy farming | ||

| 6. Farmers cry out for affordable financing | ||

| Urban and peri-urban areas have also become sources of food production through intensive investments in green houses within the urban setting. | 7. Farmers lose money through their cooperatives due to mismanagement | |

| 8. Information technology still a nightmare for farmers | ||

| 9. Free farmers from middlemen | ||

Convergences and divergences

The core present concerns convergent among all groups included the impacts of climate change, land degradation, food insecurity, inadequate governance, inadequate infrastructure, low level of financing, issues related to technology (including the dichotomy between Western and indigenous knowledge), and youth migration/brain-drain. Also, an overall vision of a peaceful and prosperous Africa capable of feeding itself and the world emerged convergently across the groups. Other convergent themes that emerged across all groups were an emphasis on education/skills, youth, women, and population empowerment, the consolidation of cooperatives and cooperation between farmers, the need for infrastructure, generating and sharing reliable data, financing, and insurance for agriculture, reaching independence from foreign donors, regional cooperation, transparency and accountability of governments—and predominantly, political will.

Participants also highlighted and tackled the enormous challenges of implementing an African agricultural transformation that is considering current societal and power structures, vested interests, the power of elites, rising inequalities, etc. Another key aspect that emerged from the discussions was a need to recognize the multiple uncertainties related to the impacts of disruptive technological changes in the near future, including those related to democracy. In table 3, we present a synthesis of convergences, grouped into three large interdependent categories: Empowerment, Partnerships for change, and Knowledge, technology and data sharing. The actions referred to here can be understood as the backbone for transformation towards the desired futures (figure 6), by participants understood as being necessary to the achievement of several SDGs. Table 3 also brings examples of existing 'seed' initiatives discussed in the groups.

Table 3. Common actions to support multiple pathways derived from the convergence analysis of the four pathways.

| Convergences (backbone actions in all pathways) | Some examples of good seeds | |

|---|---|---|

| Empowerment (youth, women and population) | Investment in education and adequate skills for agriculture that combines traditional and innovative knowledge (essential for the population empowerment and transformation of the sector). | RWEE (Rural Women Economic Empowerment) Joint Program UN-Women, WFP, IFAD and FAO. |

| Mechanisms for guaranteeing youth participation in politics. | Mastercard Foundation: Youth Africa works initiative | |

| Involvement of communities in decisions: bottom-up and top-down balance. | In Rwanda: young people (engaging) in the political system. | |

| Addressing gender issues -a constant theme in all pathways- including land tenure, finance access and political representativeness for women. | ||

| Structured markets and incentives to transform agriculture in an attractive sector for the youth (addressing the concern of out-migration). | ||

| Partnerships for change | ||

| Political will at different levels. | ||

| Proactive approaches to change among all actors and parts of the society, not relying solely on governments to initiate changes. | Land consolidation and crop intensification program in Rwanda. | |

| Consolidation of small farmers' cooperatives (from production to markets). | Government of Uganda has initiated E-voucher system invested in agro-processing facilities and distribution of inputs to farmers for increased production. | |

| Investments in physical infrastructure (roads, energy, irrigation, agro-processing, climate resilient solutions, etc) and finance infrastructure (easy access to credit and insurance for farmers). | ||

| Adequate trade agreements and development of local to global markets. | Kenyan government invests in large- and small-scale irrigation systems to reduce dependence on rain fed agriculture (1.2 million acres to date). | |

| Regional and Continental cooperation and planning (markets, governance, infrastructure, technology), including environmental concerns (conservation, climate change adaptation/mitigation). | ||

| International compromise (aligned to regional plans, alliance against corruption, aiming at independence from donors). | ||

| Knowledge, technology and data sharing | Data collection for natural resources monitoring, (agroecological) spatial zoning and regional planning. | Mobile tech-based payment/ transfer systems (similar to Kenya's MPESA, a mobile phone-based money transfer service launched in Kenya) applied to agricultural production may help farmers attain higher shared values. |

| Creation of collaboration platforms/hub for sharing best-practices. | ||

| Improvement of extension systems focusing on context-specific solutions embedded in collaboration networks. | ||

| Research and development combining traditional values and modern techniques (seeds, climate resilient practices). |

Examples of divergences (see table B.1 in the Supplementary data) related to different perspectives concerning urbanization, population growth, consumption changes, agricultural practices (sustainable intensification, agroecology), the role of different actors and agricultural systems in the future (community-oriented farming, market-oriented small-holder farming, large-scale industrial agriculture), and the role of the agriculture sector in the African economy. The discussions in the groups challenged some of the basic assumptions of existing global sustainability scenarios outlined in the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways, including massive urbanization, very low population growth, reduced area for agriculture due to the expansion of biofuels and large-scale forest restoration for carbon absorption, land-sparing approach, and drastic reduction in meat consumption. That the participants contested some key aspects of global sustainability scenarios indicates the importance of these types of cross-scale dialogues for improving the design of scenarios that can be supported (see van der Leeuw 2020) (presented in table B.2 in the Supplementary data). Box 1 presents an example of how a divergence can shed light on multiple perspectives represented in a simple influence diagram, figure 5.

Box 1. An illustration of divergences: population growth.

| The issue of population growth (and measures to control it) caused divergences in all the groups. Some viewed population growth as a threat to natural resources and food security, while others emphasized it as an opportunity to create new markets, a larger workforce, and innovative youths—reflecting the different angles of this debate in society. The Prosperous and Peaceful East African pathway story mentions this as an open issue: "... whether we should limit population or find ways to see it as an asset". Dialogue participants highlighted population as an asset in rural and urban areas, and consumption levels in rich countries as the real threat to the availability of natural resources, and food security. Counter to this, the narrative underlying sustainability-focused Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 1 (SSP1) of the global sustainability discourse proposes a drastically lower growth of population as a key premise to a sustainable future. |

| Figure 5 illustrates an influence diagram representing both these perspectives. Blue arrows portray the view that an increased population contributes to a greater work force that can bring innovations and efficiencies that could lower the consumption footprint and hence the natural resource use. The brown arrow portrays the view that a greater population causes a bigger 'consumption footprint'. Based on such divergent perspectives, one can challenge assumptions in relation to the population growth of the SSP1, and how well they will land in various geographic contexts. This is discussed in Aguiar et al (2020). |

Figure 5. Influence diagram illustrating alternative causal relationships between population growth and food security emerging from the Dialogue. The '+' signs at the arrowhead indicate that the effect is positively related to the cause (e.g., an increase in Production improves Food security ). The '–' signs at the arrowhead indicate that the effect is negatively related to the cause (e.g., increased Efficiency causes a lower Consumption footprint than what would otherwise have been the case).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable B.3 in the Supplementary data synthesizes the divergences grouped into seven categories (Urbanization, Population growth, Agricultural intensification, and practices, Actors in agriculture, Alternative diets, Markets for agricultural products, and Land-based climate change mitigation), discussing their implications for societal decisions at different political and geographical levels, and also for future scenario design. In Aguiar et al (2020), we further explore how the identified divergences can be used to create narratives for alternative target-seeking scenarios.

Figure 6. Schematic representation of the resulting convergences and divergences. The green color represents convergent elements of Desired sustainable futures, while the orange and white dots summarize decision points/branching points. Source: prepared by the authors based on Aguiar et al (2020) which was based on Fazey et al (2016) and Roy et al (2018).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageParticipants' evaluation

An evaluation of the Dialogue in the form of a written survey was submitted by 58% of the participating stakeholders (survey in Appendix C, and submitted replies in Appendix D in the Supplementary data). The results indicate that the approach was received positively and perceived as useful, discussing relevant questions and worth applying in different contexts (median 4 on a scale between 1 and 5 in the survey). Most of the respondents would also recommend the process to be used by others (median 5 on a scale of 1 to 5). Some participants had to leave early and could not participate in the evaluation, which may have affected the results.

In the following subsections, we detail selected qualitative details of the participants' responses, related to the first two of the above-mentioned premises of the study: (a) systems perspective and SDG integration, (b) multiple perspectives, and participants' ownership of the pathway narratives. It should here be noted that evaluating participatory approaches is challenging and there is a risk of over-focusing on quantitative measures. In addition, when assessing the outcomes of participatory approaches, the complexity of the context makes it difficult to trace the causal relationships between actions and outcomes (see a further discussion on this in Norström et al 2020).

Systems perspective and SDG integration

Participants' evaluations emphasized the value of 'holistic' and 'multi-sectoral approach' (indicated by the answers to the survey question 'What was the most important moment(s) for you during this workshop?': 'Holistic approach in addressing SDGs; Interdependence of SDGs').

In support of the integrative perspective, participants also noted that agriculture can enable transformations of other sectors (responses to the evaluation question 'What ideas or insights do you look forward to sharing at work?' included: 'Pathways [...] to sustainable social-economic transformation through modernizing agriculture' and 'That transforming agriculture requires a multi-sectoral approach'). This wider focus on linkages across sectors has been argued to be missing in SDG interaction studies to date (Bennich et al 2020).

Multiple perspectives and participants' ownership of the pathway narratives

Examples of participant answers to the question 'What ideas and insights do you take home from this workshop? include': 'Embracing our diversification;...'; 'The group work was nicely formed with a different range of expertise which helped the discussion among the group members.'; 'It is possible to achieve something tangible if we bring people together'.).

The participants' evaluations also suggest that the alternative futures were emerging from the realities experienced by the participants (as an example, one respondent in the evaluation referred to the dialogue as a 'People-led initiative'). Participants' ownership of the resulting pathways was facilitated by the fact that the futures emerged from a participatory process (one participant referred to as the main insight to bring from the dialogue that 'communities need to be empowered [through participative processes]'). Participants further highlighted deliberations of the future as important because they created shared understanding among participants. As an example, one of the participants answered the question 'What was the most important moment(s) for you during this workshop?' by stating 'All the interesting discussions and sharing knowledge'). The aspects focusing on creativity may have increased participants' feeling of ownership as several of the participants mentioned the letters from the future as the main highlights.

Methodological contributions

The 3H4SDG approach facilitates explorations of (a) alternative pathways to reach the SDGs in an integrated way; and (b) convergences and divergences between the pathways and across scales. By bringing an explicit recognition of conflict and tension it avoids assuming there is a pre-determined consensus that needs to be arrived at. This is in line with the 'opening up' of possible futures, in line with the sustainability pathways approach (Leach et al 2010). Conflicting problem framings are allowed to co-exist.

The politics of transformations

Pathway development and discussions on transformations, including such where the 3H4SDG is applied, involve power relationships, as systemic changes create winners and losers. Transformations are therefore not 'apolitical' but rather underpinned by political processes (Patterson et al 2017, Blythe et al 2018, Linnér and Wibeck 2019). Conflicting paradigms in the context of various international assessments such as the International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development, IAASTD (e.g., around the use of different agricultural technologies, Vanloqueren and Baret 2009), IPCC (including around the incorporation of negative emissions, Beck and Mahony 2018) and the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, IPBES (competing framings around biodiversity, Borie and Hulme 2015) are often situated within uneven processes of deliberation where resourceful actors take part besides less resourceful actors, shaping the discourses (Vanloqueren and Baret 2009, Beck and Mahony 2018).

As values and paradigms influence the behavior of global models, this needs to be acknowledged in global modeling, including those used in the context of the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (see Saltelli et al 2020 which also points to the need to acknowledge stakeholders and multiple views in model formulation). In the case of the 2030 Agenda, this risks the production of overly technocratic outlooks that do not incorporate the possibilities for radically different futures, of which some are already emphasized and desired by communities (see Wyborn et al 2020). It is here that the main strengths of the 3H4SDG approach can be found, as it explicitly highlights divergences and thereby gives room for alternative perspectives that can later be incorporated into models. However, dialogues such as the African Dialogue on the World in 2050 do not take place in a vacuum but are inevitably affected by surrounding power relations, paradigms, and perspectives. In the case study presented here, these include, e.g., who was invited to the dialogue and who was able to come.

Limitations

Reaching a desirable level of diversity of pathways that are explored may prove difficult due to various constraining factors, including time, financial capacity, geographic representation, language barriers, etc (see Turcotte and Pasquero 2001, Reed 2008).

Although the African Dialogue participants' group covered different parts of the African continent (across eleven countries) and was diverse regarding participants' origin, residence and home organization, East Africa was overrepresented, and Southern Africa was underrepresented. Furthermore, while participants came from different age groups, a majority of the participants were men, as it has proved challenging to keep a gender balance given that the positions that we recruited the participants from were primarily occupied by men. This occurred despite a conscious strategy and targeted invitations. Power dynamics affect participatory processes and demonstrate asymmetries (Cornwall 2008, Pereira et al 2020). As this is sometimes unavoidable, the process has to be carefully accounted for and should not pretend to be representative. Particularly if the group is not representative of societies. This risks the skewing of the results of the process and limits the extent to which deprived voices are heard. In our case study, it may be difficult to imagine how a women-dominated or gender-balanced group of participants would have affected the results but it is likely that such a group would better represent women's unique experiences and related perspectives. Bringing together a non-representative group of stakeholders (but one whose viewpoints are nevertheless important to engage), can still lead to an effective outcome - and bring different points of view to the forefront as is evident from the diversity of the pathways that were uncovered. Future case studies would nevertheless benefit from including follow-up workshop(s) in connection to the dialogue, in which the results can be presented and further discussed and related to existing governance processes. This conclusion has also been brought forward to the 2021–2024 XPaths project in which the approach is being used, see Box 2.

Box 2. XPaths: A collaborative research project using 3H4SDG+ dialogues in Brazil, Senegal, and Spain 2021–2024

| Inspired by the 3H4SDG method that was first applied in the case study presented in this paper, a collaborative research team was formed on reaching the SDGs in drylands with a focus on semiarid areas in Brazil, Senegal, and Spain. The research project named XPaths started in 2021 and is now in its third year. The project explores how to create inclusive pathways that will lead to achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the cases of the study areas. Just like the African dialogue presented here, XPaths takes a broad perspective - bridging local to global scales, and contrasting narratives about desired futures. Although the case studies are all drylands, they differ in income, institutions, and historical contexts. Some preliminary results from the XPaths project are available on the project web page, see https://www.xpathsfutures.org/. |

We see the overarching frame and systems perspective as a strength of the approach which has been called for elsewhere (e.g. Bennich et al 2020). It facilitates the visualization of alternatives to the prolongation of existing societal trends - which has been identified as an asset in future studies (Andersson and Westholm 2019). However, with such an overarching frame there may be few clear receivers that will implement the suggestions, and the impact is difficult to measure, and often results in 'small wins' (see also Turcotte and Pasquero 2001). Nevertheless, in other potential applications, the proposed approach is versatile enough to target particular decision-making contexts.

Although this study focuses on scenarios for achieving the SDGs, the process is generally also applicable to the globally very influential Shared Socioeconomic pathways (SSPs). Expanding the scenario space of the SSPs to include a diversity of perspectives, in particular from the Global South, was a key recommendation to improve SSPs discussed in the paper reflecting SSPs by many of their founders (O'Neill et al 2020). Thus, in this study, we have concretized how this recommendation could be carried out with a geographically and expertise-wise diverse set of stakeholders, which the SSP community could learn from. In Aguiar et al 2020, we discuss how the results presented here could be contrasted to the SSPs.

Future use of the 3H4SDG approach

The 3H4SDG approach serves as a meaningful way to provide stakeholder inputs and visioning to implementation that not only offers advice on a detailed level but enables a systems view of development. The approach can also open a critical discussion on sustainability visions that are imposed top-down. We see the approach as adaptable to different circumstances and with different themes and questions, and it has already been taken up and adopted in different settings by the Dialogue participants (Graziani 2019), and as the backbone of the more comprehensive XPaths research project (see Box 2 and https://www.xpathsfutures.org/).

Conclusions

The Three Horizons for the SDGs (3H4SDG) that is laid out in this paper is a participatory process that brings a systemic perspective to the 2030 Agenda and highlights divergent perspectives, and different views of what can be considered to be desirable futures. It can thereby be argued to democratize visioning by lifting voices previously not heard. The approach combines the Three Horizons framework (Sharpe et al 2016) with multi-scale scenario- and systems-thinking approaches, and can be adapted to a variety of contexts.

The approach has proved to have multiple assets. First, it facilitates deliberation, collaboration, and shared understanding and visioning in a diverse group of stakeholders. Second, it provides a novel way of looking at the SDGs from a systems perspective in which the Agenda is seen as a coherent whole. Third, it fosters ownership and creativity as it motivates participants to develop different forms of syntheses (including artistic ones).

The identification of convergences and divergences can be used to deliberate alternatives among diverse voices and for further specification of sustainability pathways. It also allows for comparisons with global pathways and facilitates their integration at sub-global scales. The African Dialogue case study provides examples of both convergent and divergent topics. In 2021–2024 the approach is being applied to case studies across drylands in three continents within the XPaths project.

We envision 3H4SDG to be used as a strategic tool that allows for inclusive discussions in the direction towards not only environmentally sustainable but also just, futures.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by Formas [2020-00474_Formas], a Swedish government research council for sustainable development. This paper is also supported by European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 101081661, project WorldTrans.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary data.

: Note

The authors have confirmed that any identifiable participants in this study have given their consent for publication.

Supplementary data (0.2 MB PDF)