Abstract

We study the impact of an extension of paid family leave in the Czech Republic from 3 to 4 years on children’s long-term outcomes. We find that an additional year of maternal care at age 3 has an adverse effect on children’s human capital investments and labor market attachment. Affected children are 6 percentage points less likely to be enrolled in college and 4 percentage points more likely to be not in education, employment, or training (NEET) at age 21–22. While the negative impact on education is persistent, with an 8 percentage points lower probability of completing college by the age of 27, the effect on NEET is short-lived. The results are driven by children of low-educated mothers, whose education and NEET outcomes are affected by as much as 12 percentage points. Our findings are consistent with previously documented positive effects of universal childcare on child long-term outcomes and with the fact that the extended maternal care induced by the extension of family leave led to a postponement of public kindergarten enrollment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Early childhood inputs have an important impact on children’s development, human capital accumulation, and labor market performance later in life (García et al. 2020). While there is substantial evidence that early maternal care is the most beneficial for child outcomes (Rossin-Slater 2018), other forms of childcare also become important as children grow older. Preschool education has been consistently found to improve child outcomes, particularly for children from disadvantaged families (Felfe and Lalive 2018). Extended parental care that crowds out institutional childcare can have a negative impact on child development (Canaan 2022). The impact is likely to be greater for children of low-educated parents, who on average provide lower-quality childcare and tend to stay at home with children for longer periods (Pronzato 2009; Cohn et al. 2014). Policies offering well-intentioned family leave of several years may then impede intergenerational mobility and increase educational inequality.Footnote 1 Understanding the impact of prolonged parental care on long-term child outcomes is therefore crucial not only for the design of family leave policies but also for policies affecting socio-economic mobility and inequality. However, research on the effects of parental care at preschool age is scarce, as are the potential sources of exogenous variation in the duration of prolonged parental care.

This paper provides the first evidence on the impact of full-time maternal care beyond the child’s 3rd birthday on children’s human capital investment and labor market attachment later in life. We do so by exploiting the variation in the duration of maternal care induced by the extension of paid family leave from 3 to 4 years in the Czech Republic in 1995. We find that the extended maternal care had a substantial negative impact on children’s long-term education and labor market outcomes, especially for children of mothers with lower levels of human capital.

The importance of full-time maternal care for child development decreases with the age of the child. While studies evaluating the impact of introducing or extending short family leave that increases exposure to maternal care during the child’s first year of life find a positive or no impact on child outcomes (see, for example, Carneiro et al. 2015; Dustmann and Schönberg 2012; Huebener et al. 2019; Rasmussen 2010; Dahl et al. 2016), research analyzing the extension of longer family leave does not always confirm the positive impact of maternal care. The limited evidence suggests that non-parental inputs become increasingly important beyond the child’s 2nd birthday, but knowledge about the effect of full-day parental care at later ages is lacking (see Rossin-Slater 2018; Huebener 2016 or Table A5 in Danzer et al. 2022 for an overview). While there is evidence of adverse effects of maternal care at the age of 2 on children’s test scores and schooling choices (Canaan 2022; Dustmann and Schönberg 2012), there is no research on whether these effects persist into adulthood. To the best of our knowledge, our study provides the first evidence on the impact of paid family leave longer than 2 years on long-term child outcomes.Footnote 2

The 1995 reform increased the duration of paid parental leave from 3 to 4 years while leaving the amount of the flat-rate monthly allowance essentially unchanged.Footnote 3 The take-up of paid leave effectively required that the parent did not work and that the child did not attend an institutional childcare facility. The extended leave option came into effect on October 1, 1995, and all parents with a youngest child aged 3 or less were eligible. We compare the outcomes of the first cohort of children affected by the 1995 reform with the last-unaffected cohort in order to estimate the impact of maternal care at the age of 3 induced by the family leave extension. We control for potential confounding factors with cohorts of older children, using the standard difference-in-differences methodology.

Our results suggest that the affected children are 6 percentage points (p.p.) less likely to be enrolled in college and 4 p.p. more likely to be not in education, employment, or training (NEET) at the age of 21–22. While the negative impact on education is persistent, with an 8 p.p. reduction in the probability of graduating from college by the age of 27, the effect on NEET is only short-lived. The effect is driven by children of low-educated mothers, whose education and NEET outcomes are affected by as much as 12 p.p. We find no effect of the reform on nest-leaving, family formation, or fertility at the age of 21–22. Our findings are robust to comparing the long-term outcomes of children in our treatment and control groups at the same age or at the same calendar time, and to using older cohorts as alternative control groups. Two placebo tests also confirm the validity of our findings.

Similar to the previous research (Dustmann and Schönberg 2012 and Canaan 2022), we do not observe the actual take-up of the leave by the mothers of the children whose outcomes we analyze, and therefore estimate the intention to treat (ITT) effect of the 1995 extension of family leave.Footnote 4 We provide evidence on the size of take-up by estimating the impact of the reform on eligible mothers of the same cohorts of children whose long-term outcomes we analyze when observed at the age of 3.Footnote 5 Eligibility was universal among mothers with a youngest child aged 3, and the size of take-up was larger than documented in most previous research, suggesting that the reform induced about 27% of mothers with a youngest child aged 3 to extend family leave beyond the child’s 3rd birthday.Footnote 6 We find no evidence of selectivity in take-up based on observable characteristics, including mothers’ education, or pre-reform labor market conditions.

While 4-year family leave is rare, full-time maternal care beyond the child’s 3rd birthday is not an exceptional phenomenon, especially among families with lower socio-economic status (Cohn et al. 2014). Understanding its impact on children is important for addressing issues of inequality and social mobility.Footnote 7 However, mothers who stay at home for 4 years are typically self-selected and much more likely to either extend their leave further or withdraw permanently from the labor force (Bičáková 2016). This makes it impossible to assess the impact of full-time maternal care at age 3 on long-term child outcomes separately from exposure to maternal care at later ages. The institutional context of the Czech family leave reform of 1995 seems particularly useful for this research question. The Czech Republic is a country that combines very long family leave (with a very high take-up rate) and a traditionally strong overall attachment of women to the labor force (a legacy of the communist regime). While the 1995 reform induced a high share of mothers to stay at home with their children for more than 3 years, the majority returned to the labor force by the time their youngest child was seven (Bičáková and Kalíšková 2019). This allows us to interpret our findings as the impact of extending temporary (rather than permanent) maternal care beyond a child’s 3rd birthday.

Prior to the extension of family leave in 1995, the majority of 3-year-old children were enrolled in public kindergartens. The reform thus postponed kindergarten enrollment by at least 1 year for most children whose mothers extended their parental leave. This relates our paper to a strand of literature that evaluates the impact of preschool education on child outcomes using universal childcare reforms (see Felfe and Lalive 2018 and Dietrichson et al. 2020 for an overview). Unlike existing family leave studies, which focus on children aged 0–2, this research also provides evidence on the impact of the type of care a child is exposed to between the ages of 3 and 6 on long-term child outcomes. It unanimously concludes that universal childcare has a positive effect on school progression, educational attainment and labor market outcomes, particularly for children from low socio-economic backgrounds (Dietrichson et al. 2020).Footnote 8 Havnes and Mogstad (2011) examine the impact of a large-scale expansion of subsidized formal childcare primarily replacing (non-maternal) informal care for 3–6-year-olds on children’s education and labor market outcomes. Our estimates of the impact of maternal care at age 3 that replaces care in public kindergartens turn out to be remarkably similar to that implied by their findings, in both sign and magnitude.Footnote 9 The positive effect of attending formal childcare at age 3, driven mainly by children with low-educated parents, is also confirmed by Felfe et al. (2015) and Havnes and Mogstad (2015). Finally, Bailey et al. (2021) document a considerable positive effect of Headstart, a means-tested public preschool program for children aged 3–5 in the US, on college enrollment of the affected children and their likelihood of working as adults.Footnote 10

While we attribute an important part of the negative impact of extended maternal care on the human capital accumulation and labor market outcomes of children to the postponement of enrollment in formal preschool, there may be other mechanisms at work behind our findings. In particular, we consider the indirect effects through maternal and other family outcomes, which are also likely to have been affected by the family leave reform and, at the same time, have been documented to affect child development (Canaan 2022). There is evidence of a negative, but only temporary, impact of the 1995 reform on mothers’ post-leave labor market attachment, which disappeared by the time the children entered school (Bičáková and Kalíšková 2019). We explore the potential impact of the reform on long-term household income and stability by looking at mothers’ labor market outcomes and marital status when the affected children were aged 11–17. While we find no evidence for these alternative channels, we acknowledge that the loss of 1 year of the mother’s earnings must have had a substantial impact on household income and could also have affected the quality and quantity of inputs the child received at home during the extended leave.

Our paper contributes to three distinct strands of the literature: First, we extend the research assessing the impact of family leave reforms on child outcomes (as surveyed in Rossin-Slater 2018; Huebener 2016 or Table A5 in Danzer et al. 2022) by providing evidence on the impact of a 4-year-long paid family leave on long-term child outcomes. Second, we complement the studies of universal childcare reforms (as reviewed in Felfe and Lalive 2018) by estimating the impact of postponing formal preschool education until the age of 4. Thanks to the specific institutional setting, we are able to estimate the effect of extended maternal care against a well-defined and relatively homogeneous counterfactual.Footnote 11 Namely, we compare the impact of the two dominant forms of childcare at the age of 3 (maternal care versus preschool education) prior to and after the reform, thus providing new evidence connecting the two different strands of research. Finally, the documented impact of being exposed to an extra year of maternal care instead of attending public kindergarten at the age of 3 also contributes to research on the impact of early childhood inputs on long-term child outcomes along the lines of, for example, García et al. (2020). Although we use a fundamentally different methodology, our estimates can serve as inputs to the structural models of skill production used to analyze children’s outcomes over their life cycle in this line of research.Footnote 12

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides the institutional background, Section 3 describes the data and methodology, and Section 4 presents our estimation results. Section 5 discusses the identification assumptions and examines the robustness of our estimates. Section 6 considers potential mechanisms behind our findings, and Section 7 concludes.

2 Institutional background

2.1 Family leave policies and the 1995 reform

Family leave policies in the Czech Republic include job protection, maternity benefits, and parental allowance. Parents are eligible for job-protected leave until their child’s 3rd birthday.Footnote 13 The job protection period was introduced in 1990 and has been maintained at 3 years duration since then. Mothers who have been employed for at least 270 days in the 2 years prior to a child’s birth are entitled to maternity benefits for 28 weeks (starting 6 to 8 weeks prior to birth). The maternity benefit is 70% of the woman’s salary from the last 12 months prior to the commencement of the maternity leave.

A parent caring for a child is also eligible for parental allowance, a non-means-tested flat-rate benefit. The parental allowance starts either immediately after maternity benefits end or immediately after childbirth if the mother is not eligible for maternity benefits.Footnote 14 Parental allowance is only paid for the youngest child. When a mother gives birth to another child, any ongoing payments of allowance for the older child are automatically terminated.Footnote 15

The eligibility criteria for the parental allowance at the time of the analysis required that the mother’s earnings were below a certain threshold (in 1995, the threshold was CZK 1800 per month — less than one-fifth of the average female wage then) and that the child who entitled the parent to the allowance did not attend a childcare facility.Footnote 16 Given these conditions and the very limited availability of part-time jobs in the Czech Republic, the receipt of a parental allowance in the 1990s implied that the parent was caring for a child at home and that the child was not enrolled in a childcare facility.

Until 1995, the receipt of parental allowance coincided with the 3-year period of job protection. In October 1995, the receipt of monthly parental allowance was extended until the child’s 4th birthday, thus exceeding the unchanged duration of job protection by 1 year. All parents with children under the age of 3 on October 1, 1995, were eligible for the extended parental allowance. The extension of the parental allowance was unexpected and likely led to delayed rather than immediate adjustment by mothers.Footnote 17 It was not announced until the end of May, by which time the first cohort of eligible mothers (those with children turning 3 in the fall after October 1, 1995) were likely to have already determined their return to work and their child’s preschool enrollment for the next school year starting in September.

There was also a slight increase in the monthly allowance payment from CZK 1740 to CZK 1848 in 1995, as part of the gradual valorization of the monthly allowance in the 1990s and early 2000s, but this change was negligible compared to the amount that parents gained by staying at home with a child for one more year and collecting an additional 12 months of parental allowance (see Fig. 1).Footnote 18 The total allowance available to a mother of a newborn thus increased by CZK 26,064 (about 700 EUR) and for a mother of a child who just turned 3 by CZK 22,176 (about 600 EUR). Regarding the net income effect on a mother of a 3-year-old child, who would have returned to work after the 3-year leave prior to the reform and who earned an average wage: the extension of leave until the child’s 4th birthday caused a net income loss of CZK 88,704 (about 2400 EUR), which corresponds to an 80% drop in annual income in the fourth year after childbirth.

With job protection ending at the child’s 3rd birthday and the low level of parental allowance benefits compared to the loss of income due to the absence of mother’s earnings, there were few financial incentives for Czech women to take the extended leave. Moreover, as discussed in Section 2.2, there were public kindergartens that provided affordable universal childcare of reasonable quality for children over the age of 3. However, there were other reasons that may have affected the extent of take-up, and the evidence presented below shows that the inactivity of mothers with the youngest child aged 3 increased, indeed, substantially after 1995.

First, there was a strong political and media campaign supporting the conservative norm of a mother as the primary caregiver and emphasizing maternal care as the most beneficial for preschool children that accompanied the 1995 reform.Footnote 19 The emphasis on the traditional role of the mother in the family and the importance of maternal care may also have emerged as a reaction to the norms imposed by the communist regime, which required everyone to work (unemployment was artificially kept at zero), including mothers with small children that were enrolled in large state-run nurseries and kindergartens with high child-to-teacher ratios. The take-up of extended leave after 1995 could be a result of the pressure of the campaign, or it could reflect mothers’ own pro-family preferences, which were suppressed under the communist regime or arose in response to it.Footnote 20

Second, job-protected family leave lasting several years may induce firms (especially in institutional settings where enforcement is not strong enough) to reduce the costs of long-term commitments by adjusting their organizational structure and offering women returning from leave less attractive or less stable jobs than they had before having children (see Schönberg and Ludsteck 2014, for example, for evidence on the higher probability of job loss among women who returned to work after job-protected leave).Footnote 21 Moreover, the job protection may have been also less effective in transition economies because of the unstable business environment, in which firms disappeared quickly or jobs were rationed (Kantorova 2004; Fodor 2005).

Finally, the transition period was accompanied by important structural changes in the labor market, which may also have increased the incentive for mothers with less favorable job prospects to take up the extended leave. However, the unemployment rate in the Czech Republic was still very low in 1995, starting from zero at the end of communism. We formally test this hypothesis of selective take-up driven by local labor market conditions in Section 4.1 but find no empirical support for it.

Whatever the dominant reason, the increase in inactivity among mothers with a 3-year-old youngest child was indeed substantial after the 1995, when the option of an extended leave came into force. Figure 2, which depicts the evolution of the share of inactive mothers by the age of their youngest child, suggests that an additional almost 40% of mothers whose youngest child was 3 stayed at home until the child’s 4th birthday in 1996 compared to 1994. This is only descriptive evidence, however, and may mask other underlying trends. We formally document the size of the take-up of the additional year of parental allowance in Section 4.1, where we estimate the impact of the 1995 reform on the inactivity of mothers with a youngest child aged 3, as a “first-stage” of our ITT analysis of long-term child outcomes.

Figure 2 also documents a slight increase in the inactivity of mothers with 2-year-old children after 1995. This rise could also be due to the reform. Prior to the introduction of extended leave, mothers of 2-year-olds who turned 3 by the end of the calendar year could enroll their children in kindergarten before their 3rd birthday, at the beginning of the school year in September, if there was sufficient capacity (for details on types and use of childcare, see Section 2.2) and return to work.

Finally, there was also a slight increase in inactivity among mothers of 4 and 5-year-old children, suggesting that some mothers extended their leave even beyond the 4 years of paid parental leave.Footnote 22

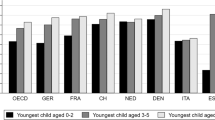

Share of inactive mothers by the age of their youngest child, 1993–1998.Note: The figure illustrates the share of mothers that are economically inactive (out of labor force) by the age of their youngest child in the 1990s. Source: Czech Labor Force Survey data (1993–1998), own calculations weighted by population weights

As a final piece of descriptive evidence on the use of extended leave, Fig. 3 addresses the question of whether all mothers who complied with the 1995 reform and extended their leave beyond the child’s third birthday stayed at home for a similar length of time or whether the increase in the share of inactive mothers of 3-year-olds masks heterogeneity in leave extension. The shares of inactive mothers by the age of their youngest child, measured in quarters of a year (the most detailed age information we can derive from the data) in 1994 and 1996 move almost in parallel between the ages of 3 and 4, suggesting that all mothers who extended their leave in response to the 1995 reform stayed at home for about three quarters of their child’s fourth year or more.

Share of inactive mothers by the age of their youngest child in quarters. Note: The figure illustrates the share of mothers that are economically inactive (out of the labor force) by the age of their youngest child (reported in quarters of a year) in the 1994 (before the reform) and 1996 (after the reform). Source: Czech Labor Force Survey data (1994, 1996), own calculations weighted by population weights

2.2 Childcare types and usage

Public childcare in the Czech Republic consists of nurseries for children aged 1–2 and kindergartens for children aged 3–5. The number of nurseries, which operated as medical facilities under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Health, was substantially reduced in the early 1990s.Footnote 23 Nursery closures were accompanied by a wider shift in family policy priorities in the 1990s, discussed above, which encouraged women to stay at home after childbirth to raise their children (Saxonberg and Sirovátka 2006).

Public kindergartens are part of the education system, subject to similar rules as other schools, under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports. The preschool education provided by the public kindergartens must follow specific guidelines (curriculum) set by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports. The aim is to ensure that the child masters the basics of key competencies (learning, problem solving, communication, social and personal skills, etc.) at an early age and thus acquires the prerequisites for lifelong learning, in order to be more successful in the knowledge society. Children in kindergartens are organized in classes, which are usually made up of children of the same age. They typically operate on weekdays (with a 4–8 week break in July and August) for a maximum of 10 h (7 am to 5 pm) per day.Footnote 24 The majority of public kindergartens charge a monthly fee.Footnote 25 Since public kindergartens are largely subsidized by the government, the cost is extremely low.Footnote 26 The maximum class size is 24 children. Preschool education in kindergartens is provided by teachers who have completed secondary or higher education with a diploma specializing in preschool pedagogy. There are 2 teachers per class, resulting in a child-to-teacher ratio of less than 12.Footnote 27

Unlike nurseries, the number of kindergartens was much less affected by the conservative policies of the early 1990s. They were both financially affordable and widely available to the vast majority of parents.Footnote 28 The slight reduction in the supply of kindergartens in the 1990s was more than offset by a sharp drop in fertility, resulting in a steady increase in overall kindergarten coverage for children aged 3 to 5 during the 1990s (see the gray bars in Fig. 4).Footnote 29

As the eligibility for parental allowance benefits required that the child was not enrolled in a childcare facility, the duration of paid parental leave and its use had a direct impact on the attendance of the youngest child at nurseries and kindergartens. Figure 4 shows the evolution of the total number of children attending public kindergartens by age on September 1 of a given year. Before the 1995 reform, the majority of 3, 4, and 5-year-old children attended kindergarten. While kindergartens are designed primarily for 3–5-year-olds, children between the ages of 2 and 6 may attend.Footnote 30

After the 1995 reform, children of mothers who took the extended family leave for the 4 years could start kindergarten only at the age of 4. The sharp drop in kindergarten enrollment by over 25% for 3-year-olds and by almost 50% for 2-year-olds, between 1994 and 1996 in Fig. 4 shows that the 1995 reform substantially affected not only mothers’ inactivity but also their children’s kindergarten enrollment.Footnote 31

Kindergarten attendance by age. Note: The figure shows the total number of children enrolled in public kindergartens by their age (age is reported as of September 1 in each calendar year) on the left vertical axis. The right vertical axis illustrates the ratio of children aged 3–5 enrolled in public kindergartens to all children aged 3–5 in the population (shown in grey bars). Source: Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports and Czech Statistical Office, own calculation

Note that the increase in mothers’ inactivity does not necessarily correspond to the change in kindergarten attendance and vice versa. Part of the observed increase in inactivity may be driven by mothers replacing other informal care for their youngest 3-year-old child with their own care by taking advantage of the extended leave after 1995, without affecting the share of children in kindergarten.

The observed increase in mothers’ inactivity and the decrease in children’s kindergarten enrollment implied by the descriptive figures presented above also differ due to the fact that the two measures are based on different datasets collected at different points in the year. Namely, while mothers’ inactivity in Fig. 2 as well as the “first-stage” results in Section 4.1 are based on the sample of women with the youngest child aged 3 (those directly affected by the 1995 reform in relation to that particular child, in order to better isolate the effect of the leave extension), the aggregate kindergarten participation rates in Fig. 4 refer to all 3-year-old children. Second, the information on mothers’ inactivity and the data on kindergarten enrollment are measured at different times of the year: while the former is measured for mothers whose youngest child is 3 years old at the time of the survey, the kindergarten enrollment rates are calculated on the basis of child’s age as recorded on September 1. Part of the increase in mothers’ inactivity should therefore also be compared with the decrease in the enrollment of 2-year-olds (who turn 3 in this school year).

Interestingly, the total number of children aged 4 and 5 attending public kindergartens remained fairly stable over the period (Fig. 4), suggesting that the children who stayed at home with their mothers at ages 2 and 3 after the 1995 reform also attended kindergarten, but only at a later age.Footnote 32 The share of children aged 6 and over in kindergarten did not change much either, suggesting that the postponement of kindergarten enrollment after the 1995 reform did not result in later school enrollment.

The evidence presented in Fig. 4 shows that the 1995 reform shifted enrollment in public kindergartens from age 3 to age 4 and shortened the total time spent in preschool education, rather than postponing the school entry age or excluding some children from preschool education altogether.

During the 1990s, the overall trend in the share of children enrolled in kindergartens among 3–5-year-olds remained fairly stable from 73 to 80% (Fig. 4), with the slight increase mostly reflecting the drop in the denominator due to the decline in long-term fertility. The consistently high shares confirm that preschool education in public kindergartens was the dominant form of childcare for this age group.

Alternative forms of childcare for children aged 3–5 were still very rare at the end of the 1990s. Kuchařová et al. (2009) surveyed a representative sample of Czech municipalities in 2002 and found that in the 497 municipalities, there were only 3 private kindergartens, 8 childcare agencies, and 4 self-help organizations focused on childcare.Footnote 33 Another survey of parents in 2005 confirms the lack of availability and use of private childcare — only 2% of parents with children aged 1–10 reported that they sometimes used a childminder to help with childcare and most of them used this form of childcare only sporadically, not on a daily basis (Ettlerová et al. 2006). It was more common to use the help of grandparents or other relatives - 20% of parents with children aged 1–10 reported that grandparents helped them with childcare on a regular basis during the week, but it is unlikely that they would provide full-time daily care (Ettlerová et al. 2006).Footnote 34

The limited information on the use of alternative forms of childcare in the 1990s suggests that the majority of children whose mothers decided to stay at home for 4 years instead of 3 after the 1995 reform would otherwise have attended public kindergarten at age 3. Therefore, care in public kindergartens represents the main counterfactual to the extended maternal care whose effects we estimate.

2.3 Education system overview

Compulsory education in the Czech Republic lasts 9 years, from age 6 to 15, and consists of primary and lower secondary education (Table 1). Almost everyone completes lower secondary school (about 99% in our sample). High school completion is also very high (over 90% in our sample). Depending on the type of school, students complete high school between the ages of 17 and 19. Students typically enroll in tertiary education at the age of 19, after graduating from Gymnasium, the general high school corresponding to the academic track. A much smaller proportion comes from technical schools.Footnote 35

Tertiary education consists of post-secondary vocational education (2–3 years) and standard higher education. The usual structure of higher education consists of bachelor’s degree programs (3–4 years), master’s degree programs (1–3 years), and doctoral programs (3–4 years). However, there are also so-called unstructured programs, such as medicine, law, or some art schools, which last 4–6 years and do not award bachelor’s degree. Tertiary education can therefore be completed at any time between the ages of 21 and 24, depending on the type of school. While students enrolled in professional tertiary programs or structured tertiary programs can obtain their first degree the age of 21, students enrolled in unstructured programs can complete their education at the age of 23 at the earliest.Footnote 36

Education is primarily provided by public institutions (including public universities at the tertiary level) and is free. Paid private schools exist at all levels of the education system but public schools serve over 90% of students.Footnote 37

3 Methodology

3.1 Data

For the main analysis of the impact of the 1995 reform on the education and labor market outcomes of the affected children in their early twenties, we use the Labor Force Survey (LFS) for the Czech Republic for the years 2010–2016.Footnote 38 Because the data do not contain information on the duration of maternal care the child was exposed to or the number of years the child attended preschool, we can only estimate the ITT effect of the 1995 reform. To explore the size of the treatment, we use the 1994–1997 LFS data to estimate the impact of the 1995 reform on the probability that a mother is at home with a 3-year-old child (see Section 4.1).Footnote 39

We focus on child outcomes at age 21–22 for two reasons: First, we can already observe the long-term measures, including high school completion rates, the share of individuals in tertiary education, and the labor market outcomes of recent high school graduates who have not enrolled in college and of children with less than high school education. Second, the share of children still living with their parents at this age is sufficiently high, which is crucial for our heterogeneity analysis of the impact of the reform by mothers’ education, since information on parental background is only available for them in the data. In the affected cohorts, about 75% of individuals reside in the same household as their mother (see Online Appendix Table A.1 for the exact share in the cohorts we use in the analysis). Although the share is relatively high, potential selection into nest-leaving may still bias our estimates from the heterogeneity analysis. We provide evidence of a zero impact of the reform on the probability of residing with one’s mother at age 21–22 in Section 5.

The identification of the last cohort unaffected by the reform and the first cohort affected is based on the exact age of the child. Since the LFS data provide age information only in full years, we use a rotational panel structure of the data and derive age in quarters of a year based on the changes observed between the two consecutive quarters.Footnote 40

3.2 Estimation strategy

We estimate the ITT impact of the 1995 reform using a difference-in-differences method, as is common in the literature (see, e.g., Dustmann and Schönberg 2012; Baker and Milligan 2015; Carneiro et al. 2015; Dahl et al. 2016; Danzer and Lavy 2018). We compare the outcomes of two cohorts of children: the last-unaffected cohort and the first cohort affected by the reform. The 1992 cohort of children (children born before October 1, 1992) was the last-unaffected cohort because mothers of children who turned 3 before October 1995 had already completed their 3 years of paid parental leave before the reform. The 1993 cohort (children born on or after October 1, 1992) were the first children whose mothers were eligible for paid parental leave until the child’s 4th birthday.Footnote 41

We compare the outcomes of the unaffected and affected cohorts at the same age (in quarters) when they are 21–22 years old.Footnote 42 Fixing age ensures that our results are not driven by age effects, but also implies that the outcomes of the two cohorts are observed at different calendar times and are therefore affected by different business cycle conditions and seasonality effects. In addition, the last-unaffected and first-affected cohorts may be born in different quarters of the year, so their outcomes may also differ due to quarter-of-birth effects.

Following the previous studies on the effects of family leave policies on child outcomes (Liu and Skans 2010; Rasmussen 2010; Dustmann and Schönberg 2012; Carneiro et al. 2015; Danzer and Lavy 2018), we control for any confounding factors, such as the quarter-of-birth or business cycle effects, using two consecutive cohorts from a neighboring year in which no policy change occurred as the counterfactual. Our identification strategy is illustrated in Fig. 5, where we clarify which cohorts are in the treatment and control groups, the before and after periods, and what we refer to as the last-unaffected and the first-affected cohort.

We define four different treatment groups based on the size of the window around the cut-off date of birth — Treat 1 are children born within one quarter before/after the October thresholds, while Treat 4 are those born within four quarters around the thresholds (see Online Appendix Table A.2 for the exact definitions of our treatment and control cohorts in the four specifications using Treat 1 to Treat 4 groups).

We present our baseline results for the four different samples, varying the width of the window around the cut-off, to explore how our estimates change with distance from the reform date and with the number of observations. The last-unaffected and first-affected cohorts in the narrower windows are closer in terms of birth and should therefore be more similar, which may help to better isolate the effect of the 1995 reform from other potential differences between cohorts that would not be captured by the control cohorts. However, the samples in the narrower windows are relatively small and some of the outcomes analyzed are quite rare (resulting in few individuals with left-hand-side variable equal to 1). Therefore, our preferred specification is the one with the broadest window. We note two other advantages of Treat 4 over the other samples: First, the last-unaffected and first-affected cohorts from 1 year before and after the reform contain birth dates evenly distributed across all four quarters of the year, so the quarter-of-birth effects should be similar in the two groups, whereas, for example, Treat 1 compares only third and fourth quarters and relies on the control groups to capture the quarter-of-birth effects. Second, the 1995 reform was likely to induce delayed rather than immediate adjustment by mothers, as discussed in Section 2.1. The policy change was not announced until May 1995, by which time mothers with children turning 3 in the Fall of 1995 were likely to have already made decisions about returning to work and enrolling their child in preschool. The reform would have no impact on these mothers of children in the narrowest specification (Treat 1).

Using the standard difference-in-differences methodology, we estimate the following equation:

where \(y_i\) is the outcome variable. We use several outcome variables: completed high school,Footnote 43 tertiary (being a student in or having completed tertiary education),Footnote 44 NEET (not in education, employment, or training), employed, unemployed, housework (inactive with housework as main activity).

\(Treat_i\) is the dummy for treated cohorts: children born before/after October 1992 have \(Treat_i=1\), while children born before/after October 1990 have \(Treat_i=0\). \(After_i\) is the dummy for being born after the October thresholds — children born after October 1990/1992 have \(After_i=1\) and children born before the October thresholds have \(After_i=0\). The coefficient of the interaction term (\(\alpha _3\)) captures the effect of the 1995 reform.Footnote 45

The control variables (\(X_i\)) are a dummy variable for gender, fixed effects for a quarter-of-birth, fixed effects for the current region of residence (NUTS 4), and fixed effects for all calendar quarter-year combinations.Footnote 46 In addition to our baseline specification, we also explore the heterogeneity of the impact of the 1995 reform on child outcomes by mother’s education and child’s gender.

In our main specification, we compare the outcomes of the first-affected and last-unaffected cohorts (born around October 1, 1992) observed at the same age (21–22), controlling for potential quarter-of-birth and business cycle effects with the control cohorts (born around October 1, 1990) observed in the same calendar year quarters as the corresponding treatment cohorts.Footnote 47 Summary statistics for the treatment and control cohorts can be found in Online Appendix Table A.1.

Our identification strategy is based on the assumption that the potential confounding factors are the same for the treatment and control cohorts, which are observed in the same year but at different ages. In particular, while outcomes are allowed to vary with economic conditions and/or quarter-of-birth effects, the impact of these confounding factors on outcomes must be age invariant.Footnote 48

While our main specification compares the outcomes of the first-affected and last-unaffected cohorts at the same age, we could also fix the calendar year for the first-affected and last-unaffected cohorts and use the control cohorts observed at the same age to control for age-related confounding factors. To check the sensitivity of our results to our identification assumptions, we also estimate this alternative specification. See Section 5.1 for a detailed discussion of this second approach, its identification assumptions, and a comparison of the results with the main specification. To examine our identification assumptions and the validity of our findings, we document the trends in cohort outcomes before and after the reform in Sections 5.2 and 5.3 and conduct two placebo-type tests in Section 5.5.

4 Results

4.1 Impact on mothers

We do not observe the use of family leave by the mothers of the children whose long-term outcomes we analyze, so we can only estimate the ITT effect of the 1995 reform on children. We are, however, able to document the actual family leave take-up by a representative sample of mothers of the last-unaffected and first-affected cohorts of children from earlier surveys of the LFS data in 1994–1997, when these children were 3. The analysis of the impact of the 1995 reform on mothers’ leave-taking can be considered as a first-stage of our estimation of the reform’s ITT effect on long-term child outcomes.

To provide information on the size of the treatment, we estimate the impact of the 1995 reform on mothers’ inactivity when their youngest child is 3. Specifically, we classify the mothers of children belonging to the treatment and control groups before and after the reform, as described in Online Appendix Table A.2, according to when their child was born.

Using the same empirical specification and DID strategy as described in Section 3.2 for estimating the impact on child outcomes, we estimate equation 1 on mothers, with the probability of being inactive as the explained variable and the same set of right-hand-side variables, just replacing child characteristics with those of mothers.Footnote 49

The results in Table 2, which presents estimates of the impact of the 1995 reform on the inactivity of mothers when their youngest child is 3 for the four different windows (Treat 1 to Treat 4), reveal that mothers’ compliance with the 1995 reform was indeed substantial. Depending on the specification, an additional up to 27 percent of mothers of the 3-year-olds extended their leave beyond their child’s 3rd birthday in response to the 1995 reform.Footnote 50 The zero impact in the narrowest window and the fact that the size of the effect increases with the width of the window is likely to be driven by the gradual adjustment of new cohorts of mothers whose children turned 3 after the 1995 reform was announced as discussed in Section 2.1.Footnote 51

Our first-stage regression suggests that the extended leave was taken by more than a quarter of all mothers with a youngest child aged 3. However, there may be selection into the treatment, as these mothers are likely to differ in terms of, for example, work-life balance preferences from those who did not take the extended leave or from those who would have been at home with a youngest child aged 3 even in the absence of the reform.Footnote 52

To shed more light on selection into treatment, Table A.3 in the Online Appendix compares the mean characteristics of inactive mothers with a youngest 3-year-old child prior to and after the reform. In our data, there are twice as many inactive mothers of 3-year-olds after the reform as before. The differences in the summary statistics for the two groups are only minor and not statistically significant.

The only characteristic for which we observe a statistically significant difference is the number of siblings, implying that mothers who took the extended leave in response to the 1995 reform had, on average, fewer children than mothers who stayed at home with the youngest child aged 3 prior to the reform. This seems to be in line with our expectations that it was mainly mothers with strong pro-family preferences (as indicated by a higher number of children) who stayed at home with a 3-year-old before the reform. The 1995 reform may also have induced mothers with fewer children, including those with an only child, to stay at home for more than 3 years.

We next test selection into take-up more formally, using our first-stage regression of the impact of the 1995 reform on the inactivity of mothers with the youngest child aged 3. We examine potential heterogeneity in take-up by allowing the impact of the reform to vary by observable characteristics and test the statistical significance of the coefficients on the respective interaction terms.

We first examine two key factors that are likely to affect selection into take-up: mothers’ education and local labor market conditions (see Table 2). More educated mothers are likely to earn more and therefore face a higher opportunity cost of not working for another year. They are, however, also more likely to have more educated partners with higher incomes and so can afford to stay at home for one more year. However, we find no heterogeneity in the extended leave take-up by mother’s education.Footnote 53

Mothers who are not subject to job protection or whose previous jobs no longer exist may be more likely to extend leave (rather than become unemployed) when jobs are scarce. We test for selection into take-up based on mothers’ job prospects by allowing take-up to vary by local labor market conditions prior to the reform, proxied by the regional unemployment rate in 1994. Interacting the reform effect with a dummy variable for regions with an unemployment rate above the median in 1994, we again find no support for selective take-up along this dimension.Footnote 54

In addition to the results on selectivity by mother’s education and by local labor market conditions, we also estimate a series of similar regressions in which we interact the effect of the 1995 reform with other characteristics available in the data, one at a time, such as marital status, number of children, spouse’s education, presence of elderly in the household, or the gender of the youngest child. None of the interaction terms, including the one with the number of siblings, turn out to be statistically significant (see Table A.4 in the Online Appendix).Footnote 55

The takeaway from our first-stage results for our ITT analysis of the impact of the 1995 reform on long-term child outcomes is therefore that the treatment was substantial (over 25 p.p. of mothers extended their leave from 3–4 years) and somewhat delayed, gradually increasing during the first year. Thus, the impact of the treatment should be most pronounced in our broader specifications (Treat 3 and Treat 4). Finally, we find no evidence of selectivity in take-up based on mothers’ characteristics and pre-reform local labor market characteristics. The information in the dataset is, however, limited and there may be other (unobserved) aspects, such as pro-family preferences, in which mothers who complied differed from those who did not.

4.2 Education outcomes of children

The main estimation results for education outcomes are presented in Table 3. The outcomes are described by two binary variables — one for high school completion and the other for enrollment in or completion of tertiary education. Our baseline specification reveals a weak negative impact of the family leave reform on high school completion (for Treat 2 and 3 specifications, see Panel A of Table 3) and a stronger negative impact on tertiary studies in our broader specifications (Treat 3 and 4, see Panel A of Table 3), suggesting a decrease in the probability of enrolling in college by about 5 p.p. This is consistent with a higher intensity of treatment in the two broader specifications (due to the gradual adjustment of the new cohorts of eligible mothers of 3-year-olds), as documented in Section 4.1. The estimate is also negative, but not statistically significant, for tertiary studies for the Treat 2 specification and for the remaining two specifications for high school completion.

When we allow the impact of the reform to vary by gender (Panel B of Table 3), the results are very similar to the baseline model and across boys and girls in terms of magnitude, especially in the broader specifications, but lose statistical significance.

Estimating the impact separately for children of low- and high-educated mothers (Panel C of Table 3) reveals that the negative effect on college enrollment is driven by children with low-educated mothers, implying that the inputs to child development provided by formal childcare at the age of 3 are superior to those provided by low-educated mothers. Our results from the two broader specifications (Treat 3 and 4) suggest that the reform reduced the probability of enrolling in college by about 12 p.p. for children with low-educated mothers. The sign of the effect in the two specifications with narrower windows around the cutoff point (1 and 2 quarters) is also negative but the estimates are not statistically significant using these smaller samples.

When we conduct our heterogeneity analysis (by mother’s education) also by child’s gender (Panels D and E of Table 3), we find that girls are much more affected by the reform than boys. In fact, the entire negative effect of the reform on college enrollment seems to be driven predominantly by girls with low-educated mothers. The estimates suggest that the reform reduced their probability of being in or having completed tertiary education at age 21–22 by as much as 17–19 p.p. The effect is again statistically significant for the broader specifications (Treat 3 and 4) but it is now also marginally statistically significant for the narrowest window (Treat 1).

4.3 Labor market outcomes of children

We next focus on the impact on the economic status of affected children at age 21–22, as measured by the following labor market outcomes: the probability of being NEET (not in education, employment or training), employed, unemployed, and inactive with housework as main activity.Footnote 56

While we find no statistically significant impact of the 1995 reform on the probability of being employed, we do find a positive impact on being NEET (Panel A of Table 4). This is consistent with the lower probability of attending college at 21–22 (documented earlier in Section 4.2) but also reflects the impact on labor market outcomes discussed below. The positive effect on being NEET is statistically significant in all specifications except the three-quarter window (Treat 3) and suggests that the 1995 reform increased the probability of being NEET by 4–7 p.p.

The results by gender are again similar for boys and girls and close to the baseline estimate in terms of magnitude but lose statistical significance (Panel B of Table 4). The estimates for the other three labor market outcomes are noisier but generally consistent with the main findings.

Looking at the heterogeneity by mother’s education (Panel C of Table 4), we find that the reform increased the probability of being NEET among children with low-educated mothers by 9–21 p.p., depending on the specification. While there is a fairly wide range in the estimated magnitudes, the effects are highly statistically significant for all treatment and control groups. On the other hand, the estimates for individuals with a high-educated mother are not statistically significantly different from zero in any specification, suggesting that the effect is again driven by children who were exposed to maternal care by a low-educated mother instead of attending public kindergarten.

When we further split our sample by the gender of the child, we find that the positive impact of the 1995 reform on the probability of being NEET is present for both boys and girls with low-educated mothers, with a larger effect for the latter (Panels D and E of Table 4). The results are only marginally statistically significant in the smaller samples of the narrower specifications but remain highly statistically significant for the broadest window (Treat 4). There is also some evidence that the increase in NEET among boys with low-educated mothers is driven by a decrease in their probability of being employed.

The reform had no impact on girls’ employment (Panel D of Table 4), suggesting that the rise in the probability of daughters of low-educated mothers being NEET was entirely driven by the decrease in the probability of their enrolling in college evidenced above. So what were these girls doing instead of going to college? The estimates in Table 5 reveal that at least some of them were more likely to be at home doing housework.

While this is only suggestive evidence, statistically significant only for the narrowest specification (Treat 1, which is based on a small sample and corresponds to the first quarter when the effect of the treatment was limited due to the gradual adjustment of mothers to the new policy), the size of the coefficient (almost 16 p.p.) is not negligible and remains positive and around 5 p.p. in all three broader specifications. In addition to the Treat 1 specification, this is also confirmed by the Treat 4 specification for all children of low-educated mothers, regardless of child’s gender, with a statistically significant coefficient and an impact of about 2.5 p.p. While the reform increased the likelihood of being NEET for both sons and daughters of low-educated mothers, we find no impact on their unemployment (see Table 5).

4.4 Family outcomes

The observed negative impact of the 1995 reform on enrollment into tertiary education and subsequent labor market outcomes could be a consequence of changes in pro-family attitudes and the preferred timing of family formation. Exposure to prolonged maternal care and the potential impact of extended leave on mothers’ careers and the division of gender roles in the family could stand behind the suggestive evidence of an increase in the probability of home production among girls. We therefore next explore whether the documented effects on education and labor market outcomes were accompanied by changes in marital status, cohabitation, or fertility decisions. Estimates of the effect of the 1995 reform on these outcomes, presented in Table 6, suggest that this was not the case. We find no impact of the reform on the marital status of affected children, on the probability that they have their own children, or on the likelihood of cohabitation at age 21–22. We also find no impact on the probability of a child living with its mother, which not only documents the zero impact of the reform on the probability of nest-leaving but also provides evidence that our heterogeneity analysis based on mothers’ education is not based on a selected sample.

4.5 Persistence and degree completion

We now complement our findings on the impact of the 1995 reform on children’s outcomes at the age of 21–22 by providing evidence on the persistence of the estimated effects at older ages. Table 7 presents the impact of the 1995 reform on the two main outcomes (tertiary education and NEET) of affected children at ages 24–25, 25–26, and 26–27, using our baseline analysis and the preferred specification Treat 4 (the one with the broadest window of 1 year on either side of the cutoff).

We focus first on education outcomes. Looking at older ages allows us to separate tertiary education enrollment and completion, as everyone could have completed their first degree by then (see Section 2.3).Footnote 57 The overall impact of the 1995 reform on tertiary education completion at the age of 24–25 is very similar to our baseline results at the age of 21–22, suggesting about a 4 p.p. reduction in the probability of completion. Interestingly, the impact on completion doubles at ages 25–26 and 26–27, indicating that affected children were not only less likely to enroll but also more likely to drop out without completing their studies than those not affected by the reform.Footnote 58

Regarding NEET, the results suggest that the impact of the 1995 reform was most pronounced among recent high school graduates at age 21–22, as documented in our baseline analysis, but disappeared at later ages. This is consistent with the difficulties that high school graduates typically face when entering the labor market for the first time. However, the difference in educational attainment and the impact of the temporary absence from the labor market after high school for those not enrolled are likely to have substantial negative effects on lifetime earnings as well as job quality, implying a persistent impact of the 1995 reform on the well-being of affected children. Table 7 also presents the results by gender. The impact of the 1995 reform on tertiary education completion is confirmed and the size of the effect is similar for girls and boys.

The results of the heterogeneity analysis (available upon request) are qualitatively similar to our main findings, confirming that the impact on tertiary education completion is driven primarily by children of low-educated mothers, but they are much noisier because the sample size of children who still live with their mothers at older ages, and thus have information about their mother’s education, declines sharply with age (to less than 10% at age 26–27).

5 Identification assumptions and robustness checks

5.1 Alternative specification

In our main specification, we compare the last-unaffected and first-affected cohorts (born before and after October 1992) at exactly the same age (measured in quarters of a year) when they are 21–22 years old. In order to filter out calendar time and quarter-of-birth effects when comparing cohort outcomes, we use the difference-in-differences approach with control cohorts of older children (born before and after October 1990), observed over exactly the same calendar time and with the same quarter-of-birth compositions. Our identification strategy is thus based on the assumption that the potential confounding factors are the same for the treatment and control cohorts observed in the same calendar year but at different ages.

To assess the sensitivity of our results to these assumptions, we conduct a robustness check that compares the outcomes of the last-unaffected and first-affected cohorts in exactly the same calendar time (but at different ages), controlling for potential age and quarter-of-birth effects using the control cohorts (born before and after October 1990) observed at the same age. Summary statistics of the treatment and control cohorts in this alternative specification can be found in Online Appendix Table A.5.

While this alternative specification allows for the age-specific impact of changes in economic conditions and quarter-of-birth effects, it makes a different restrictive identification assumption that age and quarter-of-birth effects do not vary with calendar time. In particular, outcomes are allowed to be affected by age and/or quarter-of-birth effects, but the impact of age and quarter-of-birth on these outcomes must be time-invariant. To provide an example of a violation of these assumptions, if the probability of employment changes differently with age in times of recession than in times of boom, and we observe our treated and control cohorts at different stages of the business cycle, the control group will not fully filter out age effects.

To explore the robustness of our results and to show how they vary with the various assumptions imposed, we next compare the results from the two specifications. The estimates from the main specification were presented in Tables 3, 4 and 5 in Section 4. The corresponding results using the alternative specification are reported in Tables A.6, A.7 and A.8 in the Online Appendix. Although the robustness analysis shows no effect of the 1995 reform on the tertiary-education outcome (Online Appendix Table A.6), it confirms the large and statistically significant effect of over 10 p.p. on the NEET outcome for girls with low-educated mothers (Panel D in Online Appendix Table A.7). We see similar but stronger evidence that the reform increased the likelihood of home production among girls with low-educated mothers (Panels C and D in Table A.8 in the Online Appendix). In particular, the reform’s impact on being inactive with housework as main activity among girls with low-educated mothers is highly statistically significant in all but the narrowest specification (Treat 1), suggesting an increase of 7–9 p.p.

Interestingly, the robustness results suggest that the reform reduced the probability of being unemployed among boys by about 4.5 p.p. (Panel B in Online Appendix Table A.8). This is the first finding that implies some positive effect of the reform on the labor market outcomes of affected children. While this finding is not supported by the results from our main specification, it is in line with the conclusion that the impact of the reform depended to a large extent on the mother’s educational attainment (a proxy for the quality of maternal care that substituted kindergarten attendance for the affected cohorts). Panel C of Table A.8 reveals that this negative effect on unemployment was mainly driven by children of high-educated mothers and Panel E again confirms that the effect is driven by boys. Since there is no impact on the probability of being NEET or in employment, the decrease in unemployment suggests that the sons of (mostly) high-educated mothers continued their studies, but not at university, as there is no evidence of an increase in enrollment in tertiary education.Footnote 59 Our findings on the impact of the 1995 reform on the probability of living with one’s mother, on partnership status and on family formation (considered in Section 6) are all robust to the alternative specification, confirming that the extension of family leave had no impact on any of these outcomes (Table A.9 in the Online Appendix).

5.2 Common trend assumptions

We provide further evidence on the validity of these two estimation strategies by checking their underlying common trend assumptions. Our approach assumes that the evolution of the outcome variables for the treatment and control cohorts would have been the same in the absence of the reform. We check this assumption by comparing the series of cohorts born in the pre-treatment period and thus not affected by the reform. Figure A.1 in the Online Appendix shows pre-reform cohort trends for the main specification, where the corresponding treatment and control cohorts are observed in the same calendar time (the year 2014). The figures show averages of our main outcome variables for the treatment cohorts born before October 1, 1992, and for the control cohorts born before October 1, 1990 (cohorts born one quarter before the corresponding October threshold are denoted −1, those born two quarters before the corresponding threshold are denoted −2, and so on). Both the education and labor market outcomes of the treatment and control cohorts evolve more or less in parallel over the pre-treatment period, with the exception of cohorts −2, for which the share of individuals in tertiary education is higher and the share of NEET individuals is lower in the control cohort (relative to the treated cohort) compared to what the common trend would have implied.

Figure A.2 in the Online Appendix illustrates the pre-treatment trends for the alternative specification by comparing the pre-reform evolution of the outcome variables for the treated and control cohorts observed at the same age (21). Most of our outcome variables are slightly more volatile in the treatment cohorts than in the control cohorts, so the trends are less similar than in the main specification. There is, however, one outcome variable for which the common trend seems to work better in the robustness specification - the share of individuals being inactive with housework as main activity. Recall that while the coefficients in the robustness results are not statistically significant for the education outcomes, they show much stronger evidence of a reform’s effect on the probability of doing housework than we found in our main specification. There is a trade-off in choosing between the main and alternative specifications, as each imposes a different set of potentially non-innocuous identification assumptions. Neither approach can be considered superior and their appropriateness for a particular empirical question also depends on the outcomes being analyzed. Since we are studying two types of outcomes, different assumptions may be more likely to be violated for one type than for the other: While education outcomes are likely to be less affected by current macroeconomic conditions (captured by calendar year effects), they may be more sensitive to the exact age (captured by age effects). On the other hand, comparing labor market outcomes at the same calendar time but at slightly different ages seems to be more innocuous than doing so at exactly the same age but in different economic conditions (as reflected by calendar time). This was also confirmed by the common trend assumptions of the two alternative specifications for the two types of outcomes discussed above. Accordingly, we conjecture that our main specification may be more suitable for education outcomes, while the alternative specification may be more appropriate for studying labor market effects. Although they differ in the exact magnitude and statistical significance of the estimates, they are unanimous in documenting the negative impact of the 1995 reform on the long-term outcomes of children of low-educated mothers.

5.3 Cohort outcomes’ evolution around the reform

The standard approach in the literature to graphically examine the impact of reform is to construct event study graphs (for details see, e.g., Clarke and Tapia-Schythe 2021) that show the evolution of outcomes for the treatment and control groups over a pre-treatment and post-treatment period. Unfortunately, there is no such control group in our design. Since all children born after October 1, 1992, were affected by the reform, we use cohorts born around a similar cut-off date of October 1, 1990, i.e., 2 years before the treated cohorts, as control cohorts. As a result, we are unable to plot standard event study graphs because our pre- and post-treatment periods consist of only 1 year (or 4 quarters) each. If we extend the post-treatment period beyond 1 year, the control cohorts begin to overlap with the cohorts in our treatment group.

In order to provide at least some evidence on the evolution of the two main outcome variables around the reform, Figs. A.3 and A.4 in the Online Appendix plot the shares of those enrolled in tertiary education and the shares of NEET for cohorts born up to 4 years before and 6 years after the reform (relative to the last-unaffected cohort, i.e., those born in 1991). The evolution of the share in tertiary education mainly reflects the upward trend in college enrollment driven by the long-term expansion of tertiary education in the Czech Republic over the last three decades. The slightly decreasing trend in the probability of being NEET over time may be related to the gradual transformation of the communist education system, which had an increasingly positive effect on the quality of skills acquisition of each new cohort, thus improving their future labor market outcomes. While there is no clear break in these long-term trends in 1992, there is a noticeable slowdown in the evolution of the share of tertiary educated (Fig. A.3 in the Online Appendix) and a clear upward shift in the evolution of the share of NEET (Fig. A.4 in the Online Appendix) in the 2 years after the reform. Both are consistent with our findings of a negative impact of the reform on tertiary education and a positive impact on NEET.

Based on previous research and our own results, we would expect the reform to have a larger impact on the children of less-educated mothers. Figures A.5 and A.6 in the Online Appendix replicate the evolution of the two main child outcomes by mother’s education. To the extent that the impact of the reform was weaker for those with mothers with higher levels of human capital, the cohorts of children of high-educated mothers can be seen as a “pseudo-control” group for the cohorts of children of low-educated mothers and the differences between the two groups can be interpreted as suggestive evidence of the potential impact of the reform on the latter relative to the former.

Figures A.5 and A.6 in the Online Appendix confirm the diverse evolution of the outcomes for the two groups. There is a drop in the share of individuals in tertiary education in the post-reform period for cohorts of children with low-educated mothers, while no such decrease is observed for cohorts with high-educated mothers. Similarly, the share of individuals in NEET increases after the reform for cohorts with low-educated mothers, but not for cohorts with highly educated mothers. These differences are consistent with our baseline results on the impact of the 1995 reform on child long-term outcomes and with the conclusion of our heterogeneity analysis that the estimated impacts are mostly driven by children of low-educated mothers.

5.4 Alternative control groups

In our baseline analysis, we use the cohorts born before/after October 1, 1990, as a control group for the cohorts born before/after October 1, 1992, who were the last-unaffected and the first-affected cohorts by the 1995 reform. As a robustness check of our results, we re-estimate our baseline analysis using older cohorts, namely those born around October 1, 1988, and around October 1, 1989. The estimates of the impact of the 1995 reform using these alternative control cohorts for the two main outcomes (enrollment in tertiary education and NEET) for our preferred specification Treat 4 are presented in Table 8. The results using the control group of cohorts born around 1989 are quite similar to our baseline analysis, with a statistically significant reduction of 4.3 p.p. (compared to the baseline estimate of 5.6 p.p.) in tertiary education enrollment and an increase of 4.3 p.p. (compared to the baseline estimate of 3.7 p.p.) in the probability of being NEET. The heterogeneity analysis also confirms our main findings in terms of magnitude but the education outcome for children of low-educated mothers loses statistical significance. Using even older cohorts, those born around 1988, our findings are no longer supported. We attribute this in part to the fact that the older cohorts (born 1 year before the end of the communist regime in the Czech Republic in November 1989) are simply too different from cohorts born around 1992. More importantly, the outcomes of our treatment and control groups are measured at different ages (to control for the same calendar year and quarter-of-birth effects). In our baseline analysis, the control group cohorts are observed at age 23–24, while the treatment group cohorts are observed at age 21–22. The alternative control group cohorts born around 1989 are observed at age 24–25, and the cohorts born around 1988 are observed at age 25–26, making their outcomes even more distant over the life cycle and therefore less comparable.

5.5 Placebo analysis

This section includes two placebo-type tests to check the internal validity of our results. First, we present a test of the common trend assumptions by conducting a placebo analysis of the impact of the 1995 reform on “fake” outcomes (those that the reform could not affect) and checking that it is zero Gertler et al. (2016). In particular, we estimate our baseline model with predetermined variables, namely mother’s and father’s education, as outcomes that could not have been affected by the extension of paid family leave. Table 9 confirms zero impact of the reform on these variables for all four specifications (Treat1 - Treat4), suggesting that the difference in the composition of parental education between the pre- and post-1990 cohorts in our control group is the same as that between the pre- and post-1992 cohorts in our treatment group, as described in Fig. 5.

The second test exploits a feature of our institutional setting that helps us identify a subset of treated children for whom the estimated impact of the reform should be zero and thus can be used as a placebo group. While all mothers of children younger than 3 were eligible to extend their family leave from 3 to 4 years when the 1995 reform came into effect on October 1, children with younger siblings were only affected through their younger siblings. As the entitlement to parental allowance and the restriction on the use of formal childcare only affected the youngest child in the family, children who had younger siblings and turned 3 before October 1 were affected in the same way as those who turned 3 after that date. Their mothers became all entitled to parental leave extension up to the 4th birthday o their younger siblings and under the same conditions: the mother was restricted from working and the younger sibling was restricted from attending formal childcare. There is no reason why the effect of the potential extension of maternal care for their younger siblings to 4 years should differ between these two cohorts or why children who turned 3 after October 1 should be more likely to have their kindergarten enrollment postponed. The impact of the 1995 reform on the long-term outcomes of children with younger siblings in our treatment group should be therefore zero since they were affected in the same way regardless of whether they turned 3 in the before or after period. We use this fact as the basis for our placebo test.

Unfortunately, the data do not allow us to accurately identify children in our treatment group who had a younger sibling at the time of the reform. We only observe siblings if both the children and their siblings are still living with their mother at the time we measure their long-term outcomes. Therefore, to avoid the possible bias due to selective nest-leaving, we use all children who turned 3 before and after the reform (regardless of the presence of a sibling) in our baseline estimation in Section 4. As an identification check, however, we can estimate the impact of the reform on a subset of children who still live with their parents and a sibling less than 3 years younger when they are 21–22. Since they were all affected by the 1995 reform in the same way — only through their younger siblings — the long-term outcomes of children in this subgroup who turned 3 before or after October 1 should not differ. The results of this placebo test, presented in Panel A of Table 10, confirm that, in contrast to our baseline analysis, there is indeed zero impact of the 1995 reform in this group, suggesting no difference in the outcomes of children who turned 3 before and after October 1, 1995, and had a younger sibling.

In contrast, when we exclude children who had a younger sibling at the time of the reform from our main sample, the results of our baseline specifications become even stronger, both in terms of statistical significance and magnitude (Panel B of Table 10).Footnote 60 In particular, the negative impact of family leave extension on the probability of enrolling into tertiary education rises from 5 p.p. to 8–9 p.p. in the broader specifications (Treat 3 and 4). The magnitude of the increase in the probability of being NEET at age 21–22 in response to the 1995 reform also rises, from 4 p.p. to 6–9 p.p., in the two narrower specifications (Treat 1 and 2) and remains similar in magnitude in the two broader specifications (Treat 3 and 4).

5.6 Sample selection in the heterogeneity analysis

As explained in Section 3.1, our heterogeneity analysis, which examines the effect of the reform by mother’s education, is conducted on a restricted sample of individuals who still live with their mother (for others, mother’s education is unknown). While this subsample represents as much as 75% of our main sample, the estimates may still suffer from sample selection bias if the decision to leave the parental home is affected by the reform.Footnote 61

However, we find no effect of the reform on the probability of children aged 21–22 living in the same household as their mothers when we estimate the effect on family outcomes in Section 4.4,Footnote 62 suggesting that the results of our heterogeneity analysis should not be affected by selection into nest-leaving.Footnote 63

6 Mechanisms

6.1 Extended maternal care and postponed preschool

In this section, we compare our results with previous findings and discuss the various mechanisms that could account for the negative impact of the extension of paid family leave on child long-term outcomes implied by our estimates. We start with the most obvious, exposure to full-time maternal care at age 3 and postponement of preschool enrollment, but we also discuss other factors that could lead to the same results.